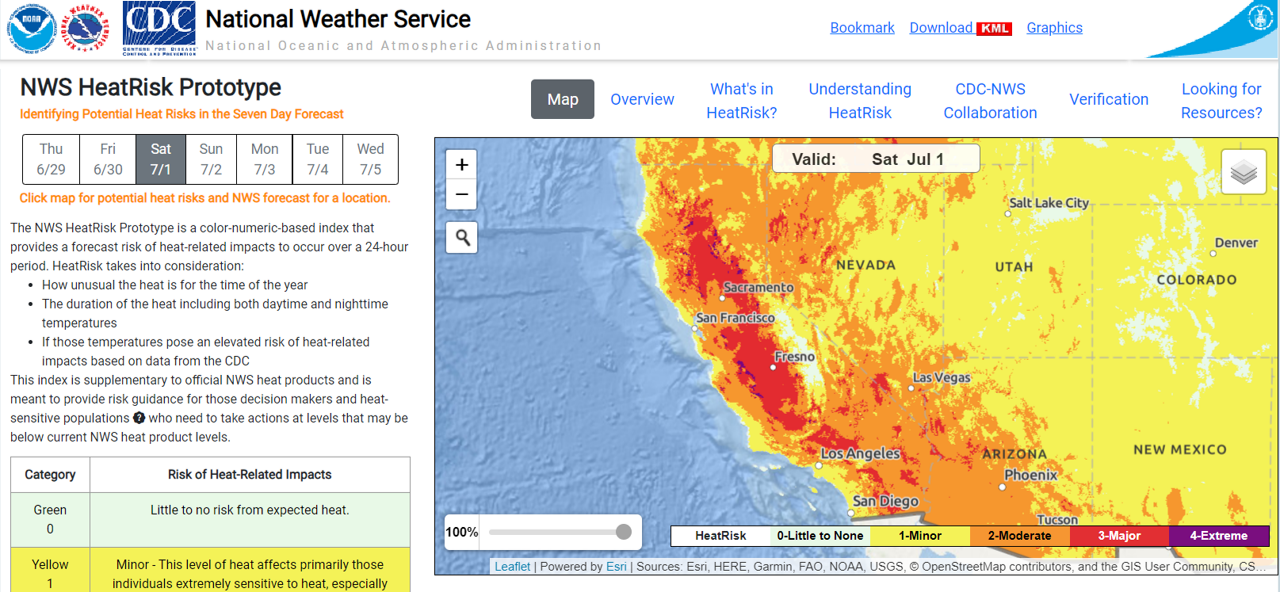

Screenshot of NWS HeatRisk forecast homepage and map. Source: National Weather Service.

Identifying Potential Heat Risks in a Seven-Day Forecast

Information below adapted from the NWS HeatRisk Overview.

Why Use HeatRisk?

-

HeatRisk is a better indicator than using temperature alone

-

HeatRisk takes into consideration how unusual the heat is for your location and time of the year

-

HeatRisk accounts for how long the heat will last (including both daytime and nighttime temperatures) and for humidity

-

HeatRisk incorporates data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to determine if temperatures pose an elevated risk of heat-related health impacts

Understanding the HeatRisk Forecast:

The National Weather Service (NWS) HeatRisk tool is a color-numeric-based index that provides a seven-day forecast of the potential level of risk for heat-related impacts to occur over each day (24-hour period). The HeatRisk tool incorporates heat-health data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to influence the local thresholds and inform the approach. That level of risk is illustrated by a color/number along with identifying the groups potentially most at risk at that level. Each HeatRisk level is also accompanied by recommendations for heat protection and can serve as a useful tool for planning for upcoming heat and its associated potential risk. Based on the NWS high resolution national gridded forecast database, a daily HeatRisk value is calculated for each location from the current date through seven days in the future. HeatRisk uses the NWS' official temperature forecast, which includes model data that takes into account urban heat islands. The National Weather Service uses this tool plus their expert judgement to declare heat advisories, watches, and warnings.

This HeatRisk tool can be used to protect lives and property from the potential risks of excessive heat, and may be especially useful for those who are more easily affected by heat or those who provide support to heat-vulnerable individuals. Weather extremes generally affect historically underserved and marginalized communities the most, and the HeatRisk forecast service ensures that communities have the right information at the right time to be better prepared for upcoming extreme heat.

How to Access the HeatRisk Tool:

-

Go to the NWS HeatRisk tool webpage

-

Click the magnifier icon and type in your address or location

-

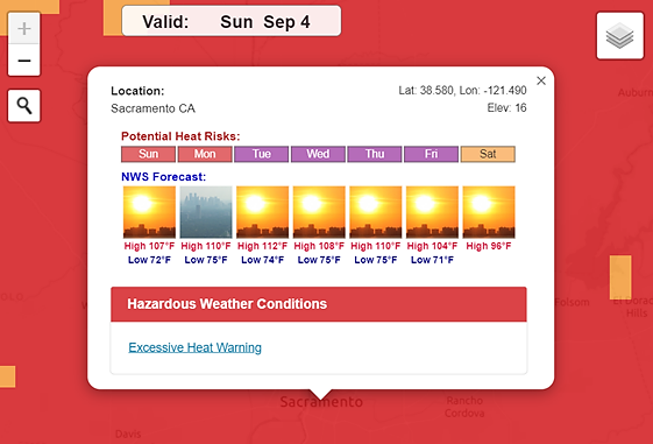

Once address / location entered, the tool will display a seven-day forecast starting with the current day, including high and low temperatures, and potential heat risk (with HeatRisk levels indicated by the colors green / yellow / orange / red / magenta). Additionally, information about hazardous weather conditions will be provided (for example, excessive heat warnings). See example screenshot for Sacramento, California below during the September 2022 heat wave:

NWS HeatRisk forecast, Sacramento, California. Accessed September 4, 2022.

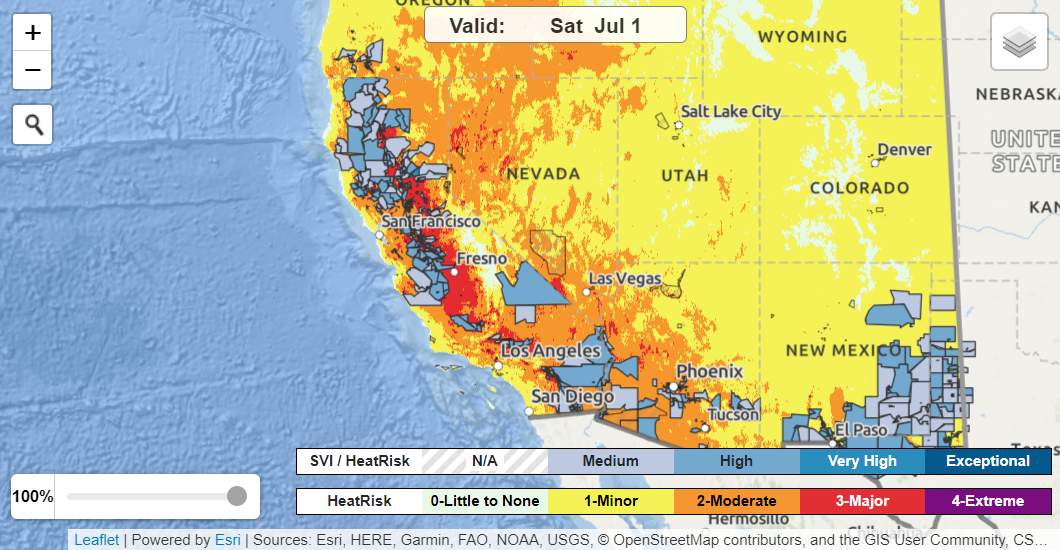

The HeatRisk tool also provides additional decision-support layers (see the “layers” icon at the upper right of the map) that allow users to view geographic boundaries (including US Counties and Tribal Lands), other NWS heat information (i.e., Heat Advisory, Excessive Heat Watch or Warning), and social vulnerability (based on the

CDC / ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index) as an overlay layer.

HeatRisk map showing Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) overlay. Accessed June 29, 2023.

-

Personal factors. Age, obesity, dehydration, heart disease[8], mental health conditions, poor circulation, sunburn, pregnancy, and prescription drug and alcohol use all can play a role in whether a person can cool off enough in very hot weather.

-

Exertion level. Even young and healthy people can get sick from the heat if they participate in strenuous[9] physical activities such as Physical Education during hot weather without gradually acclimatizing to hot conditions over a period of 1–2 weeks.

-

High humidity. When the humidity is high, sweat won’t evaporate as quickly. Evaporation of sweat is the main way the body can cool itself.

Who is most at risk to health effects of heat?

Extreme heat can affect anyone, but those with greater heat sensitivity or heat vulnerability are at an increased risk of heat illness and death. In many cases, there can be multiple and/or simultaneous factors affecting someone that increase their overall risk and vulnerability to heat-related health impacts. For example, someone can be unhoused (or live in a single room occupancy / SRO unit), work outdoors as an agricultural worker, have a chronic health condition, and have limited English proficiency – all factors that can contribute to the cumulative risk of heat illness and death.

In general, populations at greater risk of heat-related health impacts include (but are not limited to) those who:

-

Are unhoused

-

Are in particular age groups, such as older adults or infants and very young children

-

Are pregnant (extreme heat is associated with increased risk of preterm birth and stillbirth)

-

Have a disability, have access and functional needs (AFN), or are homebound

-

Are affected by chronic health conditions or other illness

-

Are affected by certain mental health or behavioral health conditions, or substance abuse disorders[10] (including those taking common

psychotropic medications or use alcohol and other substances – see next item)

-

Are taking

certain medications (like antidepressants, beta-blockers and other heart medications) or substances (like alcohol) that can interfere with the body’s internal “thermostat” or impair sweating

-

Work outdoors – especially new workers, temporary workers, or those returning to work after a week or more off (e.g., agricultural workers, construction workers)

-

Work indoors in non-cooled spaces or non-air conditioned environments (e.g., warehouse workers)

-

Work in protective service occupations, including firefighters, police officers, and emergency responders

-

Are exercising or doing strenuous activities outdoors (or indoors in spaces without adequate cooling) during the heat of the day – especially those not used to the level of heat expected, those who are not drinking enough fluids, or those new to that type of activity

-

Live alone or are socially isolated, without others to check on them

-

Live, work, or go to school in urban areas (due to

urban heat island effect), particularly areas with more asphalt and dark surfaces, and less shade, tree canopy, or green spaces

-

Live in households without air conditioning, particularly for residents on top floors of multi-story residential buildings; along with those who live in geographic areas where homes historically have not needed air conditioning (for example, coastal communities), or in circumstances where residents cannot afford to run their air conditioning

-

Are incarcerated (for more information, please visit the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s (CDCR)

Extreme Heat Prevention and Response webpage)

-

Have limited English proficiency (LEP)

-

Use electricity-dependent assistive technology and medical equipment

-

Live in mobile or manufactured homes, rental housing, or single room occupancy (SRO) units

-

Otherwise are exposed to heat or the sun, especially long-lasting heat

-

Otherwise lack access and/or mobility options to travel to public cooling facilities, shaded areas, green spaces, or other places with reliable cooling and hydration

-

Otherwise already experience social and health inequities

General Information and Recommendations:

-

For information on protecting specific populations, including

older adults aged 65+,

infants and children,

those with chronic conditions,

low-income populations,

athletes,

outdoor workers, and

pregnant people, please refer to the

CDC’s “People at Increased Risk for Heat-Related Illness” webpage (en Español). For additional guidance (including in different languages) regarding protecting infants, youth, and teens, please see the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment's (OEHHA) Children and Heat webpage.

-

For general information on protecting

people with disabilities in the face of emergencies (including heat emergencies), please refer to the resources available from

Ready.Gov and the

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

-

For information on protecting

pregnant individuals and babies, please refer to the

CDPH Safe Pregnancies in Extreme Heat webpage. Additional resources including the OEHHA fact sheet,

Pregnancy and Heat – Protect Yourself and Your Baby (PDF) and

CDC’s “Clinical Guidance for Heat and Pregnancy” webpage.

For information on protecting workers, please refer to the CDPH Worker HEAT (Heat Effects and Tracking) program webpage. Additional resources include a HRI signs and symptoms infographic, and data briefs on Occupational Heat Related Illness Emergency Department Visits, California, 2016-2021 (PDF) and Occupational Heat Related Illness Claims Among California Workers, 2000 - 2022 (PDF).

-

For additional

general guidance and tips for ways to stay safe during extreme heat, please refer to the

CDPH Extreme Heat homepage or the

CDC Extreme Heat homepage.

-

Provide heat-related health education or guidance information in multiple languages to ensure language accessibility. Consider translating and providing outreach in any language exceeding a certain minimum threshold or geographic concentration of individuals that speak that language. For example, the California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS)

determines the non-English languages (PDF) in which, at a minimum, Medi-Cal managed care health plans must provide translated written member information (see DHSC-determined Threshold and Concentration Languages for all Counties, as of July 2021).

-

Consider collaborating with other local agencies, community-based organizations, Tribes, and other stakeholders to protect community health from extreme heat to leverage resources and opportunities. For example, Public Health, Emergency Services, and other agencies at the County level can partner with city government agencies within their jurisdiction, along with Tribes, community- and faith-based organizations, and other partners to ensure coordination and collaboration regarding planning, preparedness, and response in the face of extreme heat (and other climate-related threats).

Taking Action: Considerations and Scenarios

The information below provides additional considerations and guidance on actions you can take (under different scenarios) to help keep community members safe, particularly those most sensitive or vulnerable to heat.

Scenario: If air conditioning is not available in someone’s home:

-

Keep blinds and drapes closed.

-

Put wet bandana or washcloth on your neck, wrists, or head. Use frozen items (e.g., ice cloths or towels, bags of frozen veggies, etc.).

-

Self-douse with water (e.g., using spray bottle) to keep the skin wet.

-

Take a cool shower or bath.

-

Close doors in unused rooms to keep cold air where you need it.

-

Turn on bathroom and stove top fans to suck hot air out.

-

Use your stove and oven less to maintain a cooler temperature in your home.

-

Stay cool during the nighttime, including to sleep better:

-

Wear breathable fabrics such as cotton or linen. Avoid non-breathable synthetic clothing.

-

Use breathable fabrics for bedding and sheets.

-

Avoid exercising or too much physical activity before bedtime.

-

If outdoor temperatures cool down during the evening, open windows to allow cool air in. If needed, hang a thin wet sheet or wet laundry in front of a window or fan so the air blowing inwards is cooled.

-

Watch for

signs of heat illness and seek help if needed.

Scenario: If someone lacks access to consistent housing or is unhoused:

For Those Who Can Travel to Another Location:

For Those Who Cannot Easily Travel to Another Location:

-

Encourage and facilitate buddy systems or other

arrangements for regularly checking in on heat-vulnerable individuals by family, friends, neighbors, and/or colleagues during hot weather.

-

Activate and deploy home visiting and other programs to check on people and provide relief where they are

-

This can include In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) workers, asthma home visitors, Black Infant Health home visitors, community health workers / promotores, Meals on Wheels, nurse home visitors, CalWORKs Home Visiting Program, or any other local health and human services or programs (including Child, Family, and Adult Services).

-

Partner with local / regional community-based organizations, faith-based organizations, mutual-aid networks, Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD), Community Emergency Response Teams, and other community service organizations to check on priority populations and provide services and assistance.

-

Provide water, fans, portable shade and other protective measures (e.g., hats, umbrellas, fabric shade coverings, clothes that are looser / more breathable, etc.), food and medication (especially if power is out).

Scenario: If someone is taking medication:

For people taking psychotropic medications:

For older adults taking medications:

Scenario: If someone has or cares for a pet or other animal:

-

Provide information on how to protect pets during hot weather by referring to the CDPH Protecting Your Pet During Hot Weather webpage

-

Never leave pets in a parked vehicle. Even cracked windows won’t protect your pet from suffering from heat stroke, or worse, during hot summer days.

-

Pets and companion animals feel the heat just as much as humans do and they can also suffer from heat-related illnesses. Heat stroke in pets is a life-threatening emergency and can lead to organ damage or death if not treated quickly. Know the symptoms of overheating for animals, including excessive panting or difficulty breathing, increased heart and respiratory rate, drooling, mild weakness or lethargy, stupor or even collapse, excessive thirst, and vomiting or diarrhea.

-

Help establish or provide information on pet-friendly cooling centers

For those with livestock and/or other farm animals:

Protecting Students Engaging in Sports and Strenuous Activities:

CDPH Health Guidance for Schools on Sports and Strenuous Activities During Extreme Heat

The CDPH health guidance for schools provides additional or supplemental information and guidance – it does not replace local plans. If a school or local jurisdiction has an existing heat emergency or emergency action plan, consult with the existing plan first. For California Interscholastic Federation (CIF) member schools, additional sports heat requirements may apply.

Key Take-Aways for School / Athletics Administrators:

-

Know your location’s “HeatRisk” level to determine when to cancel activities or move to alternative activities in cooled indoor spaces. If a circumstance is unclear or uncertain, cancel.

-

Be aware that multiple days of extreme high temperatures will make students and athletes more vulnerable to heat illness.

-

Always monitor for exertional heat illness. Air temperature, humidity, direct sunlight, and other factors can increase risk of heat illness.

-

Be aware that exertional heat stroke is life-threatening. Exertional heat stroke can occur within the first 60 minutes of exertion and may be triggered without exposure to high ambient temperatures.

-

Proceed with extra caution in scenarios where extreme heat occurs suddenly, lasts an extended period of time, and/or reaches new high temperatures. Generally, in these scenarios, very few outdoor activity participants (or those participating in indoor spaces without cooling) are “acclimatized.”

Protecting Workers from Extreme Heat:

Cal/OSHA Indoor Heat Illness Prevention

-

Cal/OSHA's

Heat Illness Prevention in Indoor Places of Employment regulation (PDF) applies to most indoor workplaces, such as restaurants, warehouses, and manufacturing facilities where temperatures can get high.

-

For indoor workplaces where the temperature reaches 82 degrees Fahrenheit, employers must take steps to protect workers from heat illness. Some of the requirements include providing water, rest, cool-down areas, methods for cooling down the work areas under certain conditions, and training.

-

Employers may be covered under both the indoor and outdoor regulations if they have both indoor and outdoor workplaces.

Cal/OSHA Heat Illness Prevention for Outdoor Workers (en Español)

Cal/OSHA’s Heat Illness Prevention special emphasis program includes enforcement of the heat regulation as well as multilingual outreach and training programs for California’s employers and workers. Details on heat illness prevention requirements and training materials are available online on Cal/OSHA’s

Heat Illness Prevention webpage and the

99calor.org (en Español) informational website. A

Heat Illness Prevention online tool is also available on Cal/OSHA’s website.

Guidance on “acclimatization,” or the “temporary adaptation of the body to work in the heat that occurs gradually when a person is exposed to it. Acclimatization peaks in most people within four to fourteen days of regular work for at least two hours per day in the heat.” Visit the

Cal/OSHA eTool’s

Acclimatization page.

CDC / National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) - Heat Stress

Health Care Facilities

CDPH All Facilities Letter (AFL 24-13) - Hot Summer Weather Advisory

-

This AFL reminds health care facilities to implement recommended precautionary measures to keep individuals safe and comfortable during extremely hot weather.

-

Facilities must have contingency plans in place to deal with the loss of air conditioning, or in the case when no air conditioning is available, take measures to ensure patients and residents are free of adverse conditions that may cause heat-related health complications.

-

Facilities must report extreme heat conditions that compromise patient health and safety and/or require an evacuation, transfer, or discharge of patients.

Child Care Licensees and Providers

California Department of Social Services (CDSS) - Provider Information Notice (PIN): Extreme Heat Hazard Awareness Focusing On Infants and Young Children (PDF)

-

Licensees and Providers must take precautions to ensure the health and safety of children when experiencing extreme weather conditions, such as high heat.

-

This PIN provides information about high heat hazards specific to child care providers caring for young children.

-

Per Title 22, Section 101239 for child care centers, the licensee shall maintain the temperature in rooms that children occupy between a minimum of 68 degrees F and a maximum of 85 degrees F.

Cooling Centers Guidance for Local Health Departments

CDPH Local Health Department Cooling Centers Guidance

Cooling centers (a cool site or air-conditioned facility designed to provide relief and protection from heat) are used by many communities to protect health and mitigate heat impacts during heat events, especially for high-risk populations that are disproportionally affected by extreme heat. This document provides general guidance for Local Health Jurisdictions to support a safe, clean environment for visitors and staff at cooling centers.

-

Cal OES Accessible Cooling Centers Guide (PDF) - Guide to support jurisdictions in planning for, and operating, accessible Cooling Centers that can serve people with disabilities and individuals with access and functional needs in an inclusive and equitable manner.

Health Equity Guidance for Local Health Departments

Interim Guide to Health Equity-Centered Local Heat Planning

This guide is intended as a planning resource for local jurisdictions to help with protecting the entire community from extreme heat regardless of residents’ background and access to resources, and in particular those with the least opportunity for good health. This guide is intended to assist local jurisdictions with incorporating health equity into new or existing heat planning efforts. Strategies or elements from this document can comprise a new or updated stand-alone heat plan, or be incorporated into Local Hazard Mitigation Plan updates, Climate Action & Adaptation Plans, General Plan Safety Elements, or Public Health Emergency Preparedness Plans. This resource can help facilitate partnerships between local health departments, offices of emergency services, and other local agencies.

Addressing Air Quality Impacts During Extreme Heat

-

Higher temperatures can lead to an increase in ozone, a harmful air pollutant.[17] Visit the

AirNow website to check the

Air Quality Index (AQI) in your area to determine if air quality is healthy or unhealthy, and to access resources for protecting community health from poor air quality .

-

Hotter temperatures and drought conditions can increase the risk of wildfires. Wildfire smoke can severely impact air quality locally and downwind. Heath effects from exposure to particulate matter in wildfire smoke can include eye and lung irritation, exacerbation of asthma, and other impacts.[18] Learn more about addressing the health effects of wildfire smoke here:

CDPH Wildfire Smoke - Considerations for California’s Public Health Officials (PDF).

Communicating Heat Risk

UCLA - Communicating Heat Risk: A Guide to Inclusive, Effective, and Coordinated Public Information Campaigns (PDF)

This report collects insights and guidance for communicators in an accessible, practical format that can strengthen communication efforts. It presents recommendations in five areas to support heat communicators to create more inclusive, effective, and coordinated public information campaigns.

Extreme Temperature Response Plan

CalOES - Extreme Temperature Response Plan (PDF; Annex to the State Emergency Plan)

The plan describes state operations during an extreme temperature warning and provides guidance for state agencies, local governments, tribes, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in preparation for their heat and cold/freeze response plans and other related activities. The plan establishes best practices for local governments through guidance and checklists and recognizes that some local agencies may already have a system for managing extreme temperatures. The plan utilizes the National Weather Service (NWS) forecast product HeatRisk, which provides daily guidance on potential heat risks.

Local Health Jurisdiction Response Examples from the 2022 September Statewide Heat Emergency

Madera County:

Trinity County:

-

Local protocol: Maintain open lines of communication with our utility providers to know whether they expect disruption to their systems. In this case, local utility, PG&E, is very good at communicating with their customers directly if there are any concerns. Trinity County distributes messaging via social media about staying cool and limiting outdoor activity during excessive heat. Due to the fires, Trinity County also has ‘clean air centers’ that can double as a cooling center for the public and these are also advertised to the community.

Yuba / Sutter Counties:

-

Ensure that pets are allowed at the cooling centers (indoors - not just kenneled outside)

-

Transportation is very important so ensure that local transit is open (especially during holidays and weekends)

-

Outreach to Access and Functional Needs clients and IHSS clients is important to ensure they have all the information and assistance that they need

-

Consider having specific cooling options for unhoused clients separate from general population

San Francisco City / County:

-

Developed internal Extreme Heat public health response guidance document for the Department

-

Provides information on extreme heat emergencies, heat-related health conditions, vulnerable populations, temperature thresholds, activation and notification phases, potential city-wide impacts, lead response and partner agencies, and more.

-

Key Consideration for Vulnerable Populations: Guidance for San Francisco population (and other populations and geographic locations) that have historically not experienced extreme heat events for extended durations:

-

“the population – in particular…vulnerable groups… -- has greater difficulty acclimating to long durations of extremely high temperatures. This causes an increased risk of heat stress and of heat related illness, which could subsequently result in death. Furthermore, the housing stock in San Francisco is also less likely to have central air conditioning both because of its age and because of the typically cooler climate.”

Los Angeles County

Climate Change and Health Vulnerability Indicators (CCHVIs) for California

Identifying and Prioritizing Communities with Greater Climate Change and Health Vulnerability

Utilize the

CDPH Climate Change and Health Vulnerability Indicators (CCHVIs) for California and

data visualization platform (CCHVIz) to help define the scope of climate impacts and identify the populations and locations that are most vulnerable to those impacts, including for extreme heat.

The indicators are grouped into three types:

-

Environmental or Climate Exposure Indicators, including for heat, air quality, drought, wildfires, and sea level rise.

-

Indicators that speak to a community’s

capacity to adapt to climate exposures, including things like air conditioning ownership, tree canopy, impervious surfaces, and public transit access.

-

And lastly, indicators that account for

populations with greater sensitivity to climate exposures – including children and elderly, those living in poverty, and data on race and ethnicity, linguistic isolation, disability, and more.

The data can be downloaded from the CDPH website, along with a description of why each indicator is relevant to climate change and health equity.

California Heat Assessment Tool (CHAT)

Exploring and Understanding How Extreme Heat Will Impact Specific Communities Across California Using Heat Health Data

The

California Heat Assessment Tool (CHAT) allows users to better understand the determinants of heat-related health impacts in your community and prioritize protecting those who are most vulnerable. You can use CHAT to explore how Heat Health Events (HHEs) are projected to change in your area at the census tract level (a Heat Health Event is any heat event that generates public health impacts, regardless of the absolute temperature). CHAT was built for planners, policymakers, public health practitioners and community members who are committed to mitigating the public health impacts of heat in their communities.

California Healthy Places Index (HPI): Extreme Heat Edition

Understanding Underlying Heat Vulnerability and Resilience Characteristics of a Community

The

California Healthy Places Index (HPI): Extreme Heat Edition is a tool developed by the Public Health Alliance in partnership with the UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation. The tool provides datasets on projected heat exposure for California, place-based indicators measuring community conditions and sensitive populations. It also provides a list of resources and funding opportunities that can be used to address extreme heat.

The tool can be used to:

-

Understand underlying heat vulnerability and resilience characteristics of a community

-

Identify resources to mitigate adverse effects of extreme heat

-

Prioritize public and private investments, resources and programs

UCLA Heat Maps

Find out which communities are at greatest risk of harm during extreme heat days

Developed by the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Center for Healthy Climate Solutions and the UCLA Center for Public Health and Disasters, the

UCLA Heat Maps is an interactive mapping tool for displaying heat-related health outcomes in California, showing the excess daily emergency room visits that occur on an extreme heat day compared to the usual, non-extreme heat day. It shows this excess by county and zip code. By using the map, public health professionals, emergency service providers, urban planners, legislators, health and human services providers, non-governmental organizations, and communities themselves can find out which neighborhoods across the state are at greatest risk of harm during extreme heat events.

Heat Safety Tool App (OSHA-NIOSH)

Planning Outdoor Work Activities Based on How Hot It Feels

The

OSHA-NIOSH Heat Safety Tool is a useful resource for planning outdoor work activities based on how hot it feels throughout the day. It has a real-time heat index and hourly forecasts specific to your location. It also provides occupational safety and health recommendations from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

The OSHA-NIOSH Heat Safety Tool features:

-

A visual indicator of the current heat index and associated risk levels specific to your current geographical location

-

Precautionary recommendations specific to heat index-associated risk levels

-

An interactive, hourly forecast of heat index values, risk levels, and recommendations for planning outdoor work activities

-

Location, temperature, and humidity controls, which you can edit to calculate for different conditions

-

Signs and symptoms and first aid for heat-related illnesses

Download on the Apple App Store

Download via Google Play

Key considerations for using the app (from

CDC Heat Safety Tool webpage):

-

Heat index (HI) values were created for shady, light wind conditions, so exposure to full sunshine can increase heat index values by up to 15°F.

-

The simplicity of the HI makes it a good option for many outdoor work environments (if no additional radiant heat sources are present, such as, fires or hot machinery). However, if you have the ability, NIOSH recommends using wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT)-based Recommended Exposure Limits (RELs) and Recommended Alert Limits (RALs) in hot environments.

-

Use of the HI or WBGT is important, but other factors such as strenuous physical activity also cause heat stress among workers. Employers should have a robust heat stress prevention program that ensures workers are protected.

-

NIOSH and OSHA are considering new scientific data related to the HI levels, and considering how to best incorporate the evolving science. It is important to regularly download updates to ensure you are using the latest version of the app.

Flex Alerts

Working Together to Prevent Power Outages During Extreme Heat

Issued by the California ISO, Flex Alerts are voluntary calls for consumers to conserve electricity in order to minimize discomfort, help with grid stability, and ensure the power stays for helping communities stay cool. The power grid is usually most stressed from higher demand and less solar energy between 4 p.m. and 9 p.m. During this time, consumers are urged to conserve power by:

-

Setting thermostats to 78 degrees or higher, if health permits.

-

Avoiding use of major appliances and turning off unnecessary lights.

-

Avoid charging electric vehicles while the Flex Alert is in effect.

Consumers are also encouraged to pre-cool their homes and use major appliances and charge electric vehicles and electronic devices before 4 p.m., when conservation begins to become most critical.

Consumers can sign up for Flex Alerts and participate in conserving energy when Flex Alerts are issued. A Flex Alert is typically issued in the summer when extremely hot weather drives up electricity use, making the available power supply scarce. Reducing energy use during a Flex Alert can help stabilize the power grid during tight supply conditions and prevent further emergency measures, including rotating power outages.

Sign up to receive Flex Alerts here

Learn more about Flex Alert here

National

Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS) - Heat.gov

National Heat and Health Information to Reduce the Health, Economic, and Infrastructural Impacts of Extreme Heat

Heat.gov is the web portal for NIHHIS, and is a collaboration of NIHHIS Federal partners, which include the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Housing and Urban Development, Federal Emergency Management Agency, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, Forest Service, National Park Service, Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Access

Heat.gov’s Extreme Heat Planning and Preparation resources here.

CDC

Heat and Health Tracker

The

CDC Heat and Health Tracker website provides a dashboard to explore your community’s heat exposure, related health outcomes, and assets that can protect people during heat events. Click on the "Heat and Health Index" (HHI) in the left navigation menu to access the HHI and learn more about the intersection of heat and health.

There are state grant programs available to support climate resilience efforts, including for extreme heat and community resilience planning and implementation (pending available funding -- please check the funding status for each grant program below):

Search for additional funding opportunities through the

California Grants Portal

References

[1] National Weather Service (NWS). Weather Related Fatality and Injury Statistics

[2]

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Extreme Heat and Your Health.

[3] Tracking California. Heat Related Deaths Summary Tables.

[4] Protecting Californians From Extreme Heat: A State Action Plan to Build Community Resilience. 2022. California Natural Resources Agency (PDF).

[5] Liu J, et al. 2021. Is there an association between hot weather and poor mental health outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environment International. Vol. 153.

[6] Sun K, et al. 2021. Passive cooling designs to improve heat resilience of homes in underserved and vulnerable communities. Energy and Buildings. Vol. 252.

[7] NWS. HeatRisk - Understanding HeatRisk.

[8] Note that common illnesses can also be exacerbated by extreme heat including autoimmune conditions; asthma, COPD, and allergies; migraines; heart disease; and autoimmune diseases including multiple sclerosis (MS), lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

[9] Vigorous activity is defined by the Centers for Disease Control as activities greater than 6.0 METs. Specific examples can be found

on CDC’s "How to Measure Physical Activity Intensity" webpage here.

[10] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Heat Health Awareness: Why it’s Important for Persons with Substance Use Disorders and Mental Health Conditions, Caregivers and Health Care Providers.

[11] Estimation of maximum safe indoor air temperatures is based on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) research and guidelines and the policies of other southwestern United States jurisdictions for establishing maximum safe indoor air temperatures. For more information, see the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Housing and Health Guidelines; also see code language for maximum temperature thresholds set by local U.S. jurisdictions, including Palm Springs, CA; Phoenix, AZ; Tempe, AZ; Tucson, AZ; Clark County, NV; and El Paso, Texas.

[12] US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2016. Excessive Heat Events Guidebook.

[13] CDC. Preventing Heat-Related Illness.

[14] SAMHSA. Tips for People Who Take Medication: Coping with Hot Weather (PDF).

[15] CDC. Heat and Older Adults (Aged 65+).

[16] M Alied and N T Huy. 2022. A reminder to keep an eye on older people during heatwaves. The Lancet. 3:10, E647-E648.

[17] CDC. Protect Yourself From the Dangers of Extreme Heat.

[18] California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA). Wildfires.