Valencia Branch Laboratory Issue Brief - November 2021

A one-year retrospective including inspection findings.

The State of California took proactive steps early in the pandemic when COVID-19 testing was a scarce resource. Over time, testing has evolved, and the state has continued to iterate and build upon the testing resources available to communities across California.

Summary

The Valencia Branch Lab has undergone two inspections since opening in November of 2020. One routine inspection, done for all new laboratories, and one related to a complaint investigation due to allegations of document destruction and wrongdoing within the laboratory.

This week, the California Department of Public Health's Laboratory Field Services division (LFS) issued the results of those inspections.

After multiple visits to the laboratory, and numerous correspondences, these inspections have both been closed with no sanctions imposed. The routine inspection did find multiple deficiencies, which are routinely found in laboratory inspections, related to documentation, record keeping, process, and training. The state and Valencia Branch Laboratory took these findings seriously and, as is the standard process for all labs undergoing initial inspection, in each instance PerkinElmer (operator of the Valencia Branch Laboratory) immediately worked to clarify where needed and implement improved process and documentation as necessary. All deficiencies were addressed and there was no impact to the integrity of the tests processed at the laboratory.

Specifically, in regard to the complaint investigation, Laboratory Field Services was not able to substantiate the local media outlets reporting that there was destruction of documents and data. There is no evidence to support these allegations.

As with all aspects of our COVID-19 response, we remain committed to constant improvement and will continue to look for ways to improve our testing capabilities for all Californians. We will continue to strive to create deeper and wider access to testing. Roughly 62 percent of tests performed for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) only specimen at the Valencia Branch Laboratory are among racial minorities, with 32 percent in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods based on the California Health Places Index (HPI) Quartile 1 and 25 percent in Quartile 2.

Along with widespread vaccination, testing availability remains critical to California as the state looks to regain some sense of normal life again. Reliable, timely and cost-effective test results are critical to allowing schools and many businesses to re-open and stay open with confidence as we continue to closely monitor the prevalence of COVID-19 in California.

Context

Early in the pandemic, when supply chains were stretched globally and access to testing modalities were limited, laboratories both private and public contended for scarce resources. Despite a growing number of tests having approval from federal regulators, navigating the complex nature of test specifications (sensitivity, specificity, and turnaround times) remained a challenge. This patchwork left many states ill prepared to address the rise in community transmission rates, and eventually hospitalizations. It also illustrated the complexities in acquiring, distributing and administering COVID-19 tests, while the lack of access to testing further exacerbated long-standing health inequities in low-income, minority, and rural communities.

Delays in the availability of the laboratory assay, early reported errors in test design, and an inconsistent and unstable supply chain from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) hindered state and local public health laboratories from scaling testing for months in early 2020. As with many states, California struggled to grow testing capacity and was able to perform only 2,000 tests per day in April—three months after the first case was diagnosed in the state. The early constraints in procuring swabs and specimen transport media further limited states from expanding testing. However, the consensus among public health experts was that testing and access to it was essential in changing the trajectory of the pandemic.

These challenges led California to establish the COVID-19 Testing Task Force in order to increase capacity, address supply chain disruptions and expand specimen collection sites. The Task Force was charged by Governor Gavin Newsom to make COVID-19 testing timely, equitable and cost-effective. Bringing together the expertise of public, private, philanthropic and academic partners set the foundation for California to begin increasing its capacity.

By the end of June 2020 California regularly reached daily testing numbers of 80,000 to 90,000 tests per day, but this would prove to be insufficient to meet the summer surge that followed the Fourth of July holiday. Laboratory load balancing along with exacerbated supply chain constraints for reagents and plastics (pipettes, pipette tips and test trays) placed new pressures on laboratories resulting in test turnaround times of three to seven days, when turnaround times ideally need to be within 24 to 48 hours to make testing an effective tool in slowing the spread of the virus. By October 2020, California averaged 125,000 tests per day.

As flu season approached the assumption was that healthcare providers would test for both COVID-19 and the flu due to the similar symptoms, which would only increase the demand for testing. California recognized the need to take bold action to drastically expand the state's testing capacity in order to avoid active community transmission. Expanding testing would allow the local public health departments to do more case finding to further suppress and contain the spread of the virus in order to allow for the safe reopening of the economy.

Testing Strategy

California's strategy focused on building testing with multiple modalities to ensure that there was diversity in testing, while recognizing that different types of tests play different roles in clinical and public health strategies to manage the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests are best for diagnostic purposes due to their performance (sensitivity and specificity), while antigen tests can be utilized with a higher cadence to isolate those with a high viral load. Further, it was important for the state not to depend on any single supply chain so that as shortages arose the entirety of the testing network would not be debilitated.

The state's testing strategy also recognized that testing was one piece of a multipronged mitigation approach that included contact tracing, quarantine, and isolation. Although these are independent efforts, they are interdependent as COVID-19 testing identifies individuals who have the virus, while contact tracing allows the public health system to find and quarantine individuals to halt the transmission of the virus.

As with any novel infectious disease, the government plays a significant role in developing diagnostic testing capabilities and capacity early. As testing becomes more readily available, and capacity grows within the commercial sector, the role of the public laboratories begins to shift away from diagnostic testing to a focus on surveillance testing. However, in the case of COVID-19, despite efforts to grow the capacity to over 100,000 new tests per day, this level of testing remained insufficient for safe economic reopening. The state had to adapt quickly to ensure that it was capable of meeting the moment and mitigating the spread of the virus.

Capacity

In late August 2020, with flu season approaching, Governor Gavin Newsom announced that California was building a new laboratory solely focused on COVID-19 testing. This contract with PerkinElmer, a U.S. based international diagnostic company, would allow California to process up to 150,000 COVID-19 PCR diagnostic tests per day, and provide turnaround times of under 48 hours from delivery of the sample to the laboratory. Building a new high throughput laboratory of this size and scale allowed California to control its own testing trajectory. The new laboratory was additive to the existing infrastructure of public and private laboratories performing COVID-19 testing in California.

This private-public partnership aimed to disrupt the testing marketplace by leveraging the state's purchasing power to further drive down the cost of testing and help break supply chain logjams by creating an independent supply pipeline that was reliable and had limited interdependencies. Together, alongside its private partners, the state worked quickly to identify a site, plan the design of a laboratory to meet the required testing standards, and in parallel hire qualified staff. A fully operational laboratory was constructed, and certified through the state and federal regulators, within eight weeks.

By adding this new capacity, California was able to increase testing in communities at high risk for contracting COVID-19 such as essential workers, those in congregate care settings, and communities of color. The laboratory opened at the beginning of November 2020 and in less than 11 weeks resulted over 1 million tests through a network of community-based specimen collection sites.

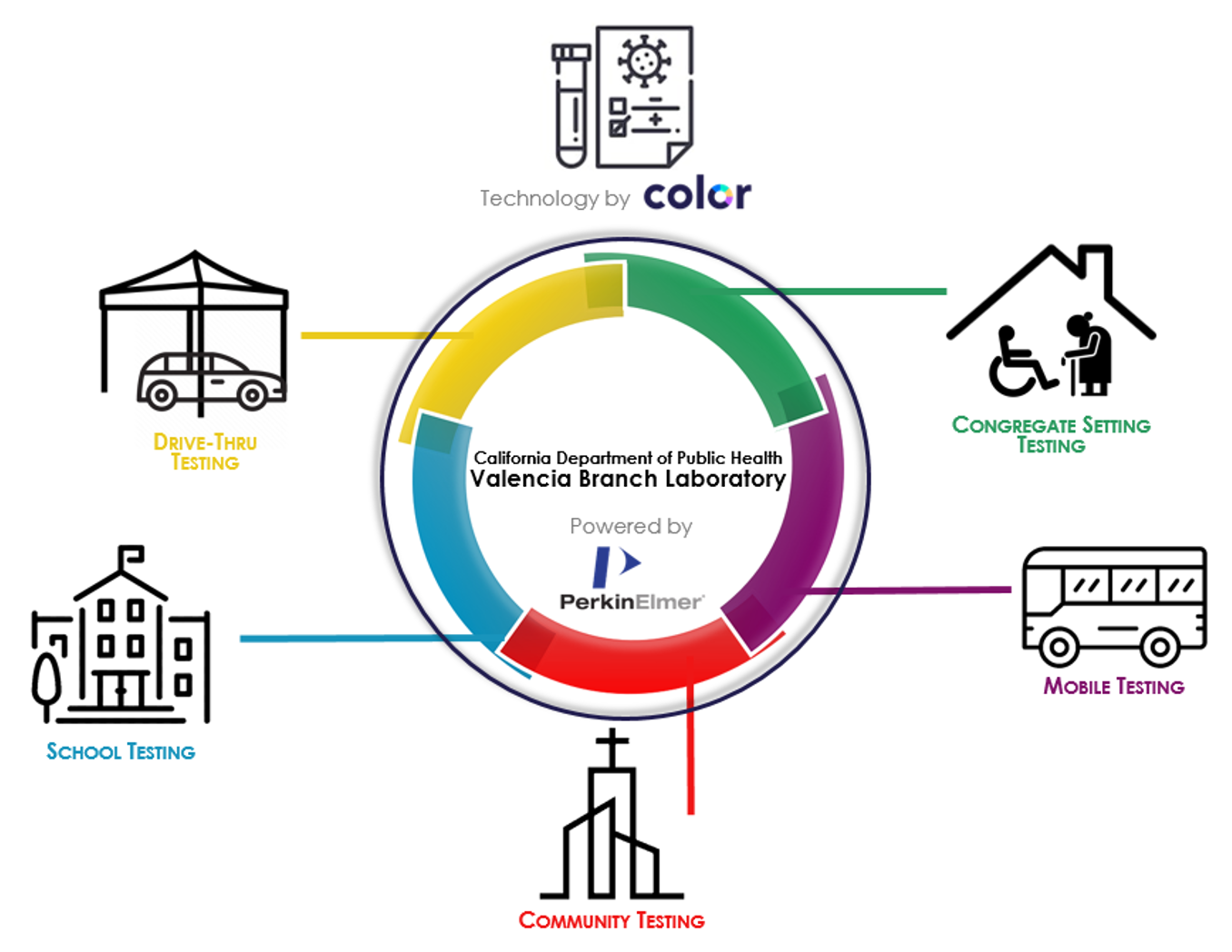

Establishing a new high-throughput laboratory that could perform PCR diagnostic tests was only one component of the strategy. It was necessary to also build an eco-system around the laboratory to access the samples and deliver results in a timely fashion (Figure 1). Building a network of specimen collection sites was essential and was perhaps more important in the effort to ensure testing was both equitable and accessible. Here another public-private partnership was forged with Color Health, a California-based technology company focused on population health. Color Health helped to create a user experience and technology platform that allowed the state to build a network of partnerships with community-based organizations to establish new sample collection sites. Utilizing a technology platform allowed the state to streamline the process and the collection of data in order to scale faster. The laboratory served as the hub and the hundreds of specimen collection sites established served as spokes, delivering on the vision of getting deeper and wider into the community in order to make COVID-19 testing readily available to Californians.

[FIGURE 1: Hub and Spoke Model]

Impact

The Valencia Branch Laboratory has increased testing availability in communities at high risk for contracting COVID-19 such as essential workers, those in congregate care settings, and communities of color. The Valencia Branch Laboratory has performed more than 5.5 million tests on samples from a network of more than 4,700 specimen collection sites developed with churches, schools, clinics, essential workplaces and community-based organizations.

This created deeper and wider access to testing. Roughly 62 percent of tests performed for PCR only specimen are among racial minorities with 32 percent in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods based on the California Health Places Index (HPI) Quartile 1 and 25 percent in Quartile 2.

Since the laboratory opened, the median turnaround time is 36 hours from collection to result. In the most recent Testing Taskforce Turn-Around-Time report (10-31-21 to 11-6-21), the VBL had an average turnaround time of 1.3 days, with 96% of all results delivered in less than 2 days. On average across all laboratories, 97% of samples were delivered in less than 2 days in that same period. All this while the Valencia Branch Laboratory accounted for more than 10% of all testing for the past several weeks and delivering more results than any other laboratory by a significant amount.

Inspections

The Valencia Branch Laboratory is subject to the oversight of both state and federal regulators. With respect to state oversight of laboratories, Laboratory Field Services regularly conducts laboratory inspections across the state. Their mission is to ensure compliance with state and federal clinical laboratory laws and regulations by performing biannual onsite inspections to ensure accuracy and reliability of laboratory test results and conducting review of laboratory performed proficiency testing results.

Laboratory Field Services conducted a routine state inspection in December of 2020. These inspections are intended to identify opportunities to improve laboratory processes and ensure the highest quality testing for all Californians. Laboratory Field Services provided PerkinElmer with identified deficiencies related to that inspection on February 19, 2021.

In the interest of transparency, on February 22, 2021 the California Health and Human Services Agency, which oversees the California Department of Public Health, made the deficiencies public. As a result of the deficiencies, the state required PerkinElmer to go through an independent inspection and accreditation process with the College of American Pathologists (CAP). The laboratory was inspected by the CAP accreditation program on March 19, 2021, and has received full accreditation, validating the validity and quality of the laboratory. CAP conducted another inspection on November 2, 2021 and confirmed continued accreditation.

In addition to the routine inspection, Laboratory Field Services conducted a complaint investigation on February 7, 2021at the request of the California Department of Public Health following reporting by a local media outlet related to allegations made regarding the training and qualifications of staff in the laboratory. There were additional allegations that were reported regarding the destruction of evidence and mishandling of specimens. As a result, the state immediately—same day as allegations were made available to the state—deployed an unannounced team of state laboratory experts to the Valencia Branch Laboratory to investigate the allegations to ensure the quality of the tests processed within the laboratory.

Timeline of State Inspections

It was important to the state that Laboratory Field Services conducted an independent inspection and investigation that was driven by the expert inspectors and their in-depth analyses. Below is an outline of the various steps in the process for context.

[TABLE 1: Timeline of LFS Inspections]

December 8 and 9, 2020

| Laboratory Field Services conducted a routine inspection of the Valencia Branch Laboratory. |

| December 16, 2020 | Laboratory Field Services conducted a follow-up visit to the Valencia Branch Laboratory. |

| February 7, 2021 | Laboratory Field Services conducted an unannounced complaint inspection. |

| February 17, 2021 | Laboratory Field Services conducted exit interview regarding December 8th and 9th routine inspection. |

| February 19, 2021 | Laboratory Field Services provided deficiency letter to the Valencia Branch Laboratory (including conditional-level deficiencies leading to a finding of immediate jeopardy) regarding the routine inspection. |

| March 1, 2021 | Valencia Branch Laboratory responded to the February 19 deficiency letter provided by Laboratory Field Services. |

| March 5, 2021 | Laboratory Field Services conducted a follow-up visit to the Valencia Branch Laboratory. |

| March 8, 2021 | Valencia Branch Laboratory submitted additional responses to Laboratory Field Services. |

| March 11, 2021 | Valencia Branch Laboratory submitted additional responses to Laboratory Field Services. |

| March 19, 2021 | College of American Pathologists inspected Valencia Branch Laboratory at the request of the state and Laboratory. |

| March 30, 2021 | Valencia Branch Laboratory, at the request of Laboratory Field Services, submitted additional responses to the original routine inspection from December 8th and 9th. |

| April 22, 2021 | Laboratory Field Services provided deficiency letter to VBL (including conditional-level deficiencies leading to a finding of immediate jeopardy) regarding the complaint inspection. |

May 3, 2021 | Valencia Branch Laboratory sent the response to the complaint investigation from February 7, 2021. |

| May 14, 2021 | College of American Pathologists issued Certificate of Accreditation |

| May 17, 2021 | Laboratory Field Services requested additional information. |

| May 24, 2021 | Valencia Branch Laboratory sent response to May 17, 2021 request. |

| June 8, 2021 | Laboratory Field Services responded to Valencia Branch Laboratory submission of May 24, 2021 (routine inspection) with multiple requests, including a request to supplement the assay validation. |

| June 18, 2021 | Valencia Branch Laboratory provided a validation plan. |

| July 3, 2021 | Valencia Branch Laboratory requested an extension of the deadline for re-validation. |

| July 21, 2021 | Laboratory Field Services agreed to extend the deadline related to the June 8, 2021 request to August 20, 2021. |

| August 20, 2021 | Valencia Branch Laboratory submitted the response as per the extended deadline. |

| October 8, 2021 | Laboratory Field Services requested further documentation regarding complaint investigation. |

| October 18, 2021 | Valencia Branch Laboratory responded to the Laboratory Field Services request of October 8th, 2021. |

| October 21, 2021 | Laboratory Field Services issued a "Notice of Intent to Impose Sanctions". |

| October 27, 2021 and November 2, 2021 | Valencia Branch Laboratory submitted response to the "Notice of Intent to Impose Sanctions". |

| November 2, 2021 | College of American Pathologists conducting a standard re-inspection of Valencia Branch Laboratory, confirming continued accreditation. |

| November 10, 2021 | Laboratory Field Services conducted an onsite visit of the Valencia Branch Laboratory and subsequently notified the Laboratory of the withdrawal of its intent to impose alternative sanctions based upon the demonstrated correction of the condition level deficiency. Laboratory Field Services also notified the Valencia Branch Laboratory of the closure of both the routine and complaint investigations.

|

Findings

This week, the California Department of Public Health's Laboratory Field Services division (LFS) issued the results of their inspections. After multiple visits to the laboratory, and numerous correspondences, these inspections have both been closed with no sanctions imposed. The routine inspection did find multiple deficiencies related to documentation, record keeping, process, and training. The state and Valencia Branch Laboratory took these findings seriously and, as is the standard process for all laboratories undergoing initial inspection, in each instance PerkinElmer (operator of the Valencia Branch Laboratory) immediately worked to clarify where needed and implement improved process and documentation as necessary. All deficiencies were addressed and there was no impact to the integrity of the tests processed at the laboratory.

Specifically, in regard to the complaint investigation, Laboratory Field Services was not able to substantiate local media reports that there was destruction of documents and data. There was no evidence to support these allegations.

As California Health and Human Services Agency Secretary, Dr. Mark Ghaly, stated in February, "One incorrect test result is one too many. California takes these findings seriously and has been working hand in hand with PerkinElmer from the beginning to ensure Californians have the accurate, timely, high-quality test results." Dr. Ghaly went on to say that "when we opened the laboratory, we committed to improving on our efforts to ensure we are delivering the best possible services." As a result, the laboratory has addressed all regulatory findings and received third party accreditation as well.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION:

Presumptive Positive

The PerkinElmer assay has received Emergency Use Authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to result cycle threshold (Ct) values up to 42 as positive. In plain language, these values provide a measure of the viral load in the specimen. At Valencia Branch Laboratory, Ct values less than 37 were resulted as positive and Ct values above 42 were resulted as negative. Tests with Ct values between 37 and 42 were resulted as inconclusive. While each laboratory and the assay they use are different, this Ct cut-off is in alignment with other COVID-19 testing laboratories who typically use a Ct cut-off in the 33-37 range. Additionally, other laboratory kits are less sensitive per FDA data.

This approach was based on recommendations from laboratory experts as the assay was sensitive enough to detect viral presence, but not enough to determine the clinical relevance, infectiousness, or the possibility of illness due to that level of viral presence. This had real-world implications as a positive test result could mean the individual being tested may not be able to work or a child not be able to go to school.

In mid-December of 2020, the laboratory worked with local partners to revise the language used for results to make it clearer to patients what they needed to do. Specifically, results that had a Ct value between 37 and 42 were relabeled and resulted as "presumptive positives." The intent here was to ensure that the patient had clear instructions on what to do next. The results clearly outlined that all patients with a presumptive positive result were instructed to isolate and be retested by having a new specimen collected.

For those patients with Ct values between 37 and 42, a second specimen allows us to more definitely determine if the patient was truly negative or positive. A change in their Ct value, up or down, can indicate where they are in the timeline of infection and give a more accurate result related to their infectiousness. Often, an individual late in their infection or having only a mild infection can result initially with a high Ct value (indicating a lower viral load), and the second specimen increases in Ct value above the threshold to a result of not-detected.

Costs

It is important to note that the contract with PerkinElmer was structured in such a way that the state pays based on volume. While the maximum value of the signed contract was $1.7 billion, the state did not provide PerkinElmer with $1.7 billion. Instead, the state is invoiced monthly by PerkinElmer and pays based on laboratory capacity and volume used. As a result, to date, the state has paid PerkinElmer $716 million. These costs are then recouped through claims submitted to FEMA or individual health insurers. To date, FEMA has approved $684 million in claims submitted alone.

The state has established two pricing structures. $55 for all community and employer based testing programs, and $21 for school based testing programs. More importantly, the price per test includes more than just the specimen processed in the laboratory. It includes the specimen collection kit, the full courier service (from specimen collection site to laboratory), technology platform, insurance billing, onsite training, and resulting support.

Auto Renew

As we approach winter, the state is preparing to respond to a variety of scenarios should we experience another surge in cases. We have learned over the last two years that COVID-19 takes advantage when we put our guard down. As a result, the state chose to allow the auto renew provision in the contract with PerkinElmer to take effect to ensure we had the capabilities in place for a potential surge. The contract still includes strong termination provisions and allows the state to terminate the contract without cause with a 45-day notice.

Lessons Learned

As with all aspects of the COVID-19 response, this has been an iterative and agile process that the state continues to work on based on lived experiences and new evidence. However, the experience in California can serve as a model for other states, and the federal government for how to scale testing by leveraging local community partners to increase flexible specimen collection methods and utilize the new laboratory to ensure cutting edge testing techniques are utilized. The federal government recently used this model as a way to create regional laboratory hubs for school testing capacity.

- Utilize community organizations to help scale specimen collection. Partnering with local public health departments and community-based organizations to expand testing sites enabled the state to ensure that testing was accessible to Californians. More importantly, it allowed the state to expand testing with local partners who were trusted in the community and familiar to those looking for testing. However, standardizing the onboarding process and providing simple and user-friendly training material was critical. A simple to navigate playbook with hands-on technical assistance allowed local partners to navigate what might be considered a daunting task.

- Build flexible specimen collection options to address local needs. California's communities are diverse both in their geography and population and therefore a one size fits all approach to specimen collection was not scalable. California looked to establish four testing options: pedestrian fixed site; drive-through fixed site; traveling teams; and mobile buses. Collectively these options enabled local partners, including local public health departments, to build specimen collection sites that best met the need of the people in their community. The state further leveraged data to help local partners be better informed about how to scale the availability of testing in zip codes that had sporadic or limited testing capabilities by developing a health equity metric.

- Iterate on laboratory capabilities to expand new testing modalities. The science is rapidly evolving with COVID-19, requiring the state and its partners to be nimble and iterative. The Delta variant has proven that the virus can and will mutate. Some of these strains might be more infectious and thus travel faster or may eventually become resistant to the vaccine. Therefore, PerkinElmer and the state have established a genome sequencing capability at the laboratory to actively track the mutations and transmissibility of the virus and its possible defense against the vaccines. As needed, additional technologies like sample pooling and multiplexing (such as adding influenza A and B to the test) may be implemented.

These lessons are based on California's experience over the past year. However, paramount to the above is the development of a private-public partnership that is nimble and iterative in order to rapidly respond to the constantly evolving nature of the pandemic. Adapting to local conditions and improving processes along the way ensure that COVID-19 testing is both person-centered and data-driven.

Discussion

There is hope that with widespread vaccination the state will curb the pandemic. However, it will take months before enough Californians are fully vaccinated to develop herd immunity and stop the spread of COVID-19. Even after getting both doses of the vaccine, it is possible, though not likely, to get COVID-19. Testing, similar to masking and physical distancing, will remain an important public health tool and an aspect of the response that will continually be built upon.

Innovation must continue in various aspects of COVID-19 testing. It will be important to continue to expand on specimen collection modalities, while also focusing on laboratory processing to ensure results are provided timely while the validity of the test is preserved. For example, use of alternate forms of collection methods such as group observed nasal swabbing, advances in extraction speed, use of different and smaller quantities of consumables, and developing efficient informatics tools are additional innovations or advances that will drive the market. Collectively these efforts will help ensure that testing becomes more timely, equitable and cost-effective.

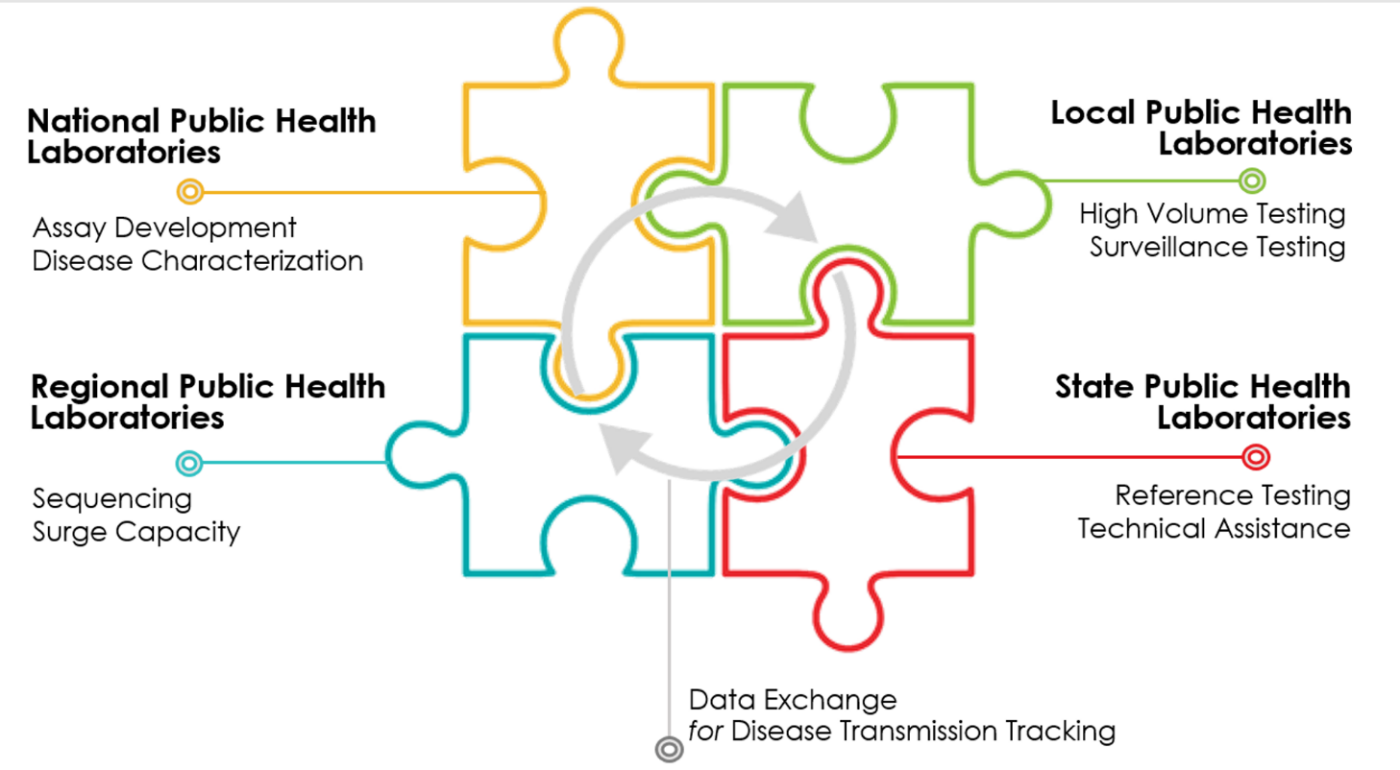

Building regional laboratory hubs across the United States, similar to the efforts underway in California, can drastically expand the access to testing and prepare the United States for future infectious disease outbreaks (Figure 2). Perhaps more challenging is the organization of local partners to serve as specimen collection sites in order to utilize the laboratory capacity and capabilities. There must be a deliberate and coordinated effort to focus on equity by ensuring that specimen collections sites are available in zip codes both disproportionately impacted by the virus and who have limited access to testing. Forging strong and nimble public-private partnership is paramount as government cannot do this alone.

[FIGURE 2: Public Health Laboratory Network]

As vaccination rates continue to rise, monitoring the data and adjusting the cadence for testing, will be important. A tailored approach, not a one size fits all approach, that looks at setting and exposure risk will help ensure that testing resources are being deployed with intention and that case finding continues to be leveraged to mitigate the spread of the virus among populations who are unvaccinated.

Finally, capitalizing on the laboratory infrastructure built by the COIVD-19 pandemic as part of the recovery is vital to building a public health laboratory network for infectious diseases across the country for future novel infectious viruses and outbreaks. Permanently adding regional capacity so that these laboratories have the ability to test across local jurisdictions allowing for timely assays and laboratory surge capacity to expand testing.

Conclusion

California seized on the opportunity to leverage its people, innovation and diversity to not only expand laboratory testing capacity, but the availability of specimen collection sites in neighborhoods that were disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Just as it has responded to past challenges, California is confronting the pandemic with resolve, perseverance, innovation and leadership. This blueprint can serve as a model for other states, and the federal government, in how to scale testing that is both accessible and equitable.

Please go to the Valencia Branch Laboratory Inspection Documents page for a complete list of documents.