Related Materials:Interim Guidance for Ventilation, Filtration, and Air Quality in Indoor Environments (ca.gov) | AFL 21-08 |

All Guidance |

More Languages

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the need for skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), long-term care facilities, hospices, drug treatment facilities, and homeless shelters to employ effective resident isolation strategies to prevent transmission of viruses through the air. These facilities must continue to be prepared to isolate residents who have, or are suspected of having, COVID-19 or any other infectious disease that spreads through the air. This document describes several methods that can help prevent transmission of infectious, aerosol-transmissible respiratory viruses within the close quarters of residential facilities by modifying the environment and enhancing ventilation.

This document is based on the consensus recommendations of ASHRAE[1] and ASHE[2] healthcare engineers and the requirements of the

Cal/OSHA Aerosol Transmissible Diseases (ATD) Standard. Under the ATD standard, facilities must place residents who have, or are suspected of having, an airborne infectious disease in an airborne infection isolation room (AIIR), unless one is not available. For novel and unknown pathogens (including SARS-CoV-2), facilities must place residents in an AIIR, unless doing so is not feasible.

These exceptions to providing an AIIR do not apply to aerosol generating procedures, such as CPAP, BiPAP, or nebulizer treatments, which may create higher levels of infectious aerosols.

When a true AIIR is not available, or when it is not feasible to place a resident who has, or is suspected of having, COVID-19 in a true AIIR or area, the ATD standard requires employers to provide other effective control measures in addition to respiratory protection for staff when entering an isolation room/area.

To protect staff and residents outside the isolation area, additional control measures are needed. Further examples of other effective control measures are described in the below Q&A, including temporary isolation practices to effectively prevent disease transmission to vulnerable residents and staff. For emergency preparedness, it is important for facilities to develop multi-disciplinary teams (infection preventionists, facilities management staff, engineers/industrial hygienists, Director of Nursing (DON), administrator, medical director, etc.) that will implement these solutions to promptly isolate residents as soon as infection is suspected/confirmed to protect staff and prevent secondary infections.

Questions & Answers

What is the importance of room ventilation and how does it affect indoor air quality in isolation areas?

In addition to prompt isolation of residents who have, or are suspected of having, COVID-19, improving general ventilation throughout a facility, as described in the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) document: Improving Ventilation Practices to Reduce COVID-19 Transmission Risk in Skilled Nursing Facilities, is a crucial step in limiting transmission to other residents and staff.

Since SARS-CoV-2 spreads primarily through inhalation of infectious aerosols present in indoor air, specific ventilation and indoor air quality practices that reduce the concentration of virus accumulating in the air of isolation areas and other resident spaces are needed to prevent spread from both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. Although all areas of a facility that are frequented by residents will benefit from improved ventilation, isolation areas should be prioritized.

The goals of improving ventilation and indoor air quality in isolation areas are as follows:

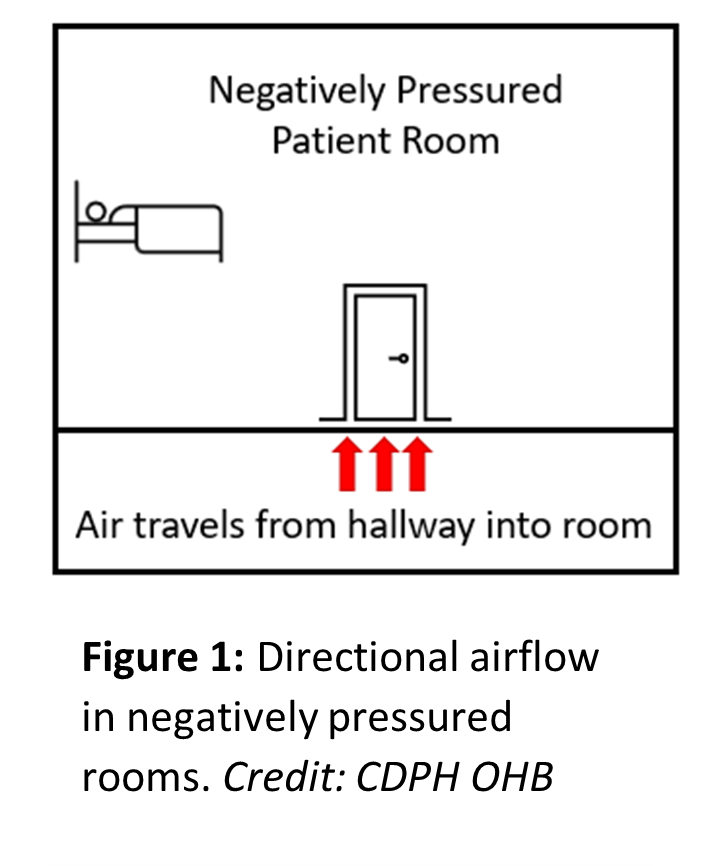

To create directional airflow from clean areas (i.e., the corridor) to less clean (i.e., sick patient rooms) so that infectious particles do not spread from an isolation room or area throughout the facility and are, if possible, exhausted directly to the outdoors.

To provide sufficient outdoor air needed to effectively dilute infectious virus particles in the isolation room or area.

To provide a high level of filtration to remove infectious particles from air in the isolation room or area.

What are CDPH recommendations for ventilation when a true AIIR is not available and transferring the patient is not feasible?

In facilities where true AIIR are not available and transferring residents with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 is not feasible, other effective control measures are required by the ATD standard. CDPH recommends the following control measures when isolating residents:

Continuously provide a minimum of six air changes per hour (ACH). At least two ACH should be provided by outdoor air introduction into the space and the rest via filtered air from the mechanical ventilation system or portable air cleaners. See CDPH “Interim Guidance for Ventilation, Filtration, and Air Quality in Indoor Environments" for information on how to calculate ACH.

Consult with experienced professionals to evaluate the possibility of preventing air in temporary isolation rooms or areas from being recirculated to other sections of the facility through the Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) system, e.g., by sealing off return air vents. Air from these rooms should be exhausted directly to the outdoors or filtered through a high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter directly before recirculation.

Create negative pressure inside the room, if possible.

If all the above measures cannot be implemented immediately, at a minimum CDPH recommends:

How can negative pressure be used to promote effective isolation conditions?

To prevent spread of virus from an isolation room or area to other areas of the facility, airflow exhaust from the space should be increased to create negative pressure inside the room. Increasing the exhaust of air out of the room can be achieved by adding equipment to move air out of the room or modifying the existing exhaust ventilation to increase the fan speed and volume of air it moves. This creates negative pressure in the room so that clean air from other areas of the facility moves toward the isolation zone. Under these conditions, air from the isolation area contaminated with infectious particles is less likely to move into the corridor or other areas to potentially infect others. After creating these conditions, it is important to regularly (i.e., daily while housing infectious patients) verify that negative pressure conditions are being maintained via the methods outlined later in this document.

What are my options when setting up temporary patient isolation areas?

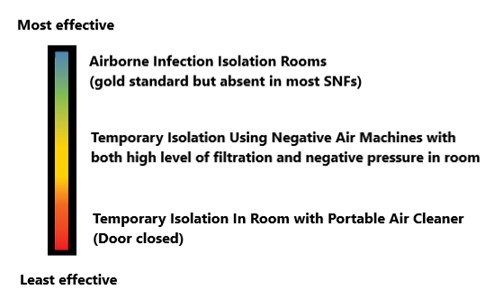

Due to the lack of AIIRs in SNFs and other facilities, it is necessary to use other effective control measures to limit the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission from positive patients in the facility. As Figure 2 indicates, there is a continuum of interventions that goes from most effective to least effective. Facilities should be prepared to employ temporary isolation rooms or areas using these strategies.

Figure 2: Options for patient isolation ranging from most to least effective at

preventing transmission. Credit: CDPH OHB

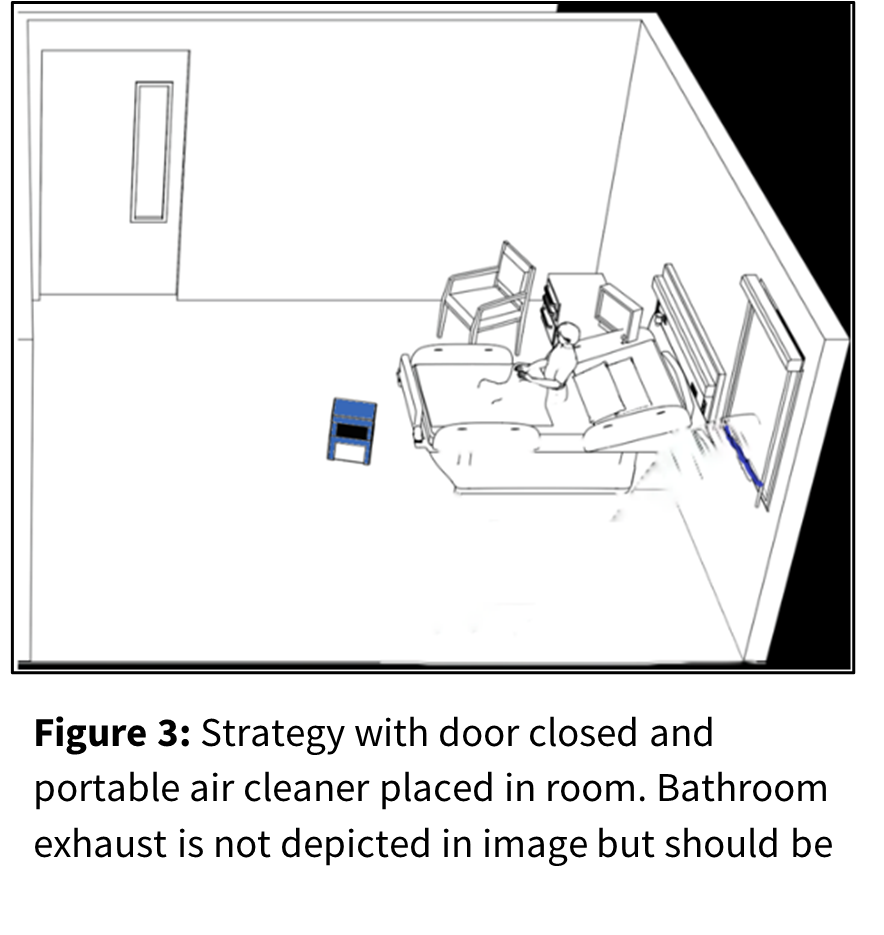

Easiest to implement: Portable air cleaners with bathroom exhaust in patient isolation rooms

The easiest strategy on this spectrum is to place the patient in a single occupancy room with the door closed to help create a barrier to the hallway. In addition, install and continuously run a portable air cleaner (PAC) with a HEPA (high efficiency particulate air) filter inside the room. The PAC offers filtration of the air in the room to reduce the “build-up” of virus particles in the patient’s room.

This approach should be supplemented by running the bathroom exhaust fan constantly if the room has a dedicated bathroom exhaust. The bathroom fan exhausts air outdoors, which can help create a slight negative pressure in the bathroom. This helps prevent air from travelling to the hallway.

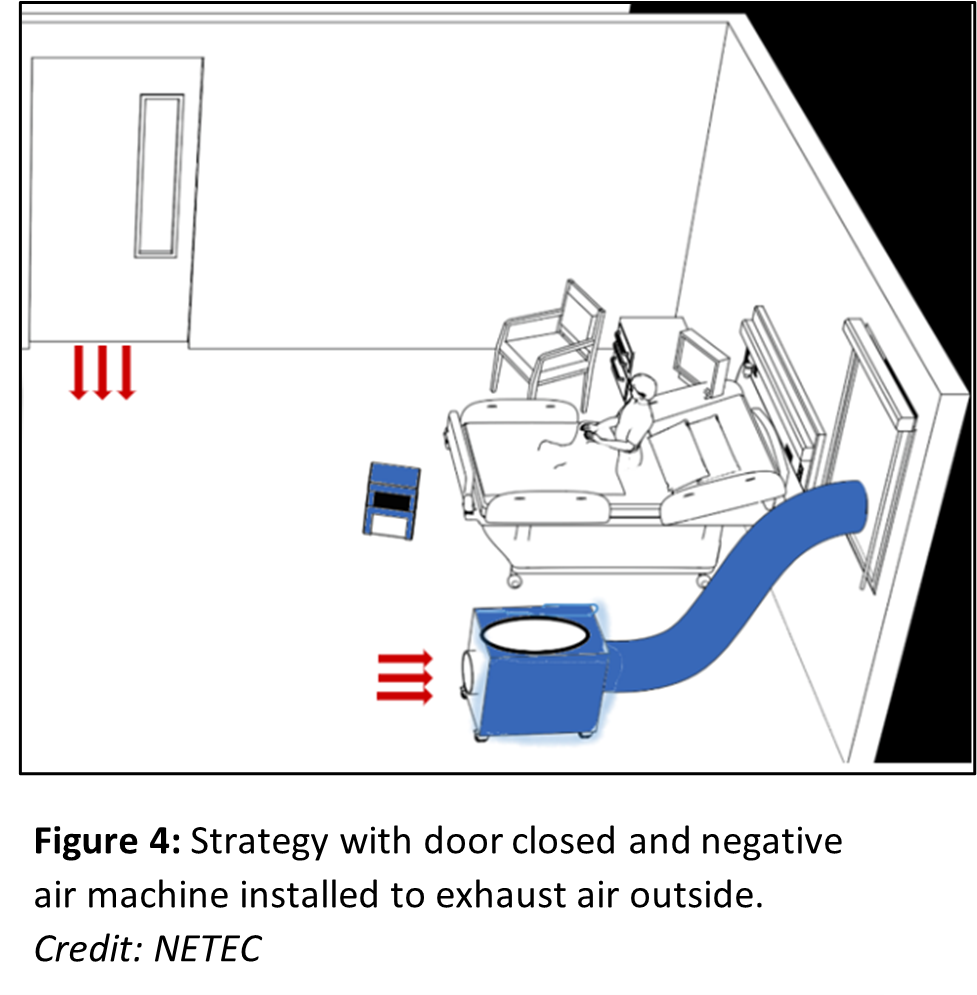

More effective: Temporary isolation with negative air machines

A more effective strategy to create temporary isolation employs a negative air machine if the patient room has a window or other means to exhaust air to the outside. This method relies on keeping the door closed as much as possible or erecting a temporary barrier and installing a negative air machine with HEPA filter.

This machine draws in room air, then filters and exhausts the air outside of the room to the outdoors. This generates negative pressure in the room, which creates an air curtain barrier between the room and the hallway while also increasing dilution in the room. This only works if the room has a window or other outlet to expel the air out of the room using the ductwork attached to the back of the air machine.

The window is removed and the opening is covered with a window adapter. The exhaust duct from the machine is placed through the window adapter with an airtight seal. If there is not a window or other outlet, both

ASHE and

CDC (see references) provide alternative options for temporary isolation environments using negative air machines. Note that negative air machines should be installed in consultation with licensed HVAC professionals to ensure their use does not upset the ventilation or air balance in other parts of the facility.

Figure 4 above shows a low-cost negative air machine installed in a resident's room. The room also has a PAC. For a higher cost, negative air machines can be purchased that provide both a high level of filtration in the room and can exhaust air out through a window adapter.

How can I verify that a negative pressure/proper directional airflow in a patient room has been created?

Upon creating a temporary isolation environment with negative pressure, it is important to use pressure measurement tools to verify that negative pressure has been created. Negative pressure can be verified in the following ways:

Differential pressure monitors (acceptable negative pressure is -0.01" of water or more negative).

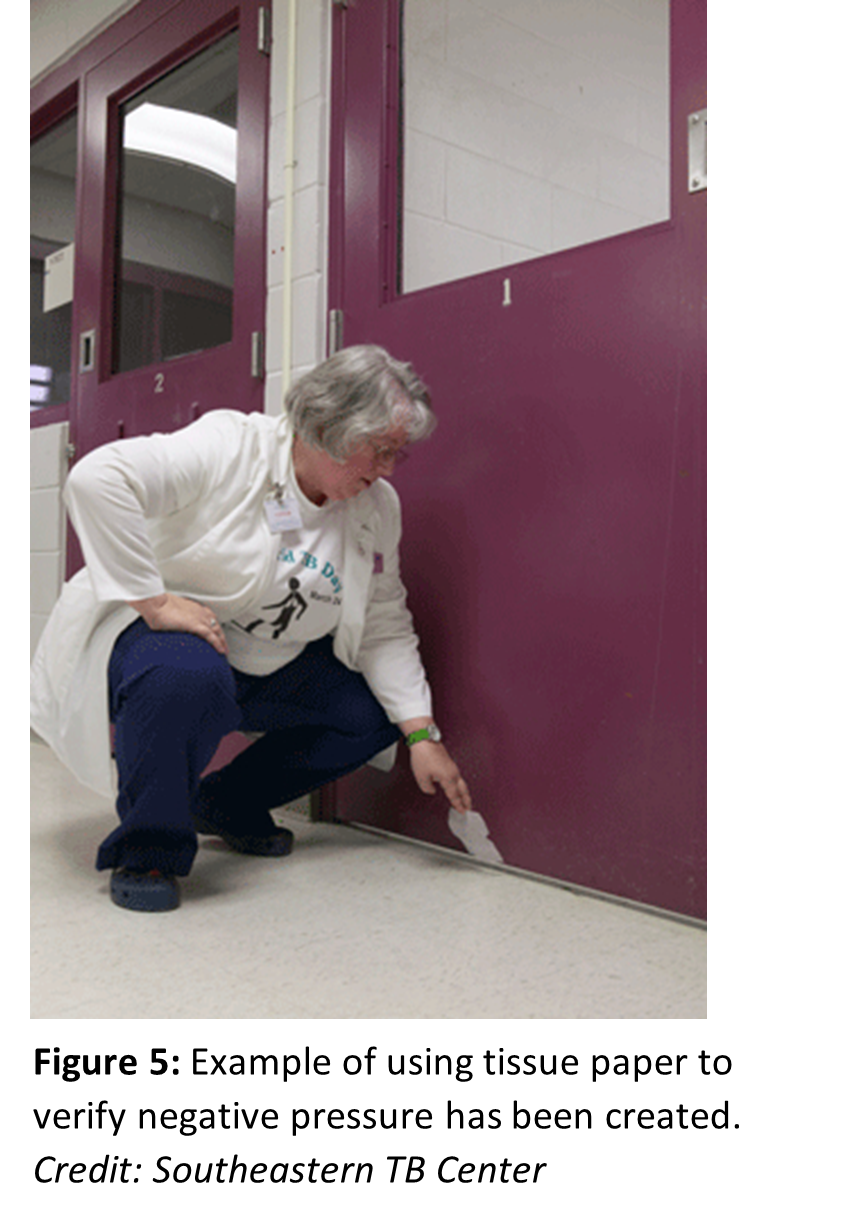

Use a piece of tissue or a non-toxic smoke to confirm that negative pressure is being maintained. Hold the tissue or release the smoke outside of the room at the base of the door and see if it drawn under the doorway into the room

Pressure conditions should be checked daily or more often if conditions change that may alter airflow and room pressure. Opening windows in an isolation area may change pressure conditions and is not advised if a facility is trying to create a negative pressure environment for patient isolation within a room or area.

Are temporary isolation areas using plastic barriers allowed in healthcare settings?

Plastic barriers are permitted by

HCAI and can be useful tools to help create isolation areas within a facility. They can be installed to create physical separation between an isolation area and other vulnerable residents and staff. They can also be used to create anterooms (enclosures just outside the isolation room or area) to provide a partial barrier to airflow. Opening doors to the isolation room may allow infectious virus to escape, but an anteroom can help contain the infectious virus by acting as an airlock to help maintain directional airflow from clean (hallway) to less clean (isolation) areas.

Anterooms, if added, are best used in addition to strategies that provide high filtration in the isolation room and that create an inward flow of air into the isolation room. As mentioned above, directional airflow, from a positive to negative pressure space, has been found to be effective in containing respiratory aerosol movement from patient rooms to adjacent corridors.

Before installing plastic walls or partitions in a facility, consider ventilation to ensure the partitions are not preventing adequate airflow to all areas of a facility. Healthcare facilities should consult the latest letters released by

HCAI and

CDC on the use of temporary plastic barriers. HCAI describes when/whether they will review projects that alter existing resident or patient rooms to provide temporary isolation of COVID-19 patients in their “Policy Intent Notice 4" (reference provided below). Another consideration regarding plastic barriers is whether they brush against a person's body or clothing as they pass through, leading to potential contamination and spread of microorganisms transmitted via direct contact. Consider using rigid materials and/or constructing plastic barriers in a manner that will avoid contact with people passing through them.

Are there additional tools that can be used to improve air quality in isolation rooms/areas?

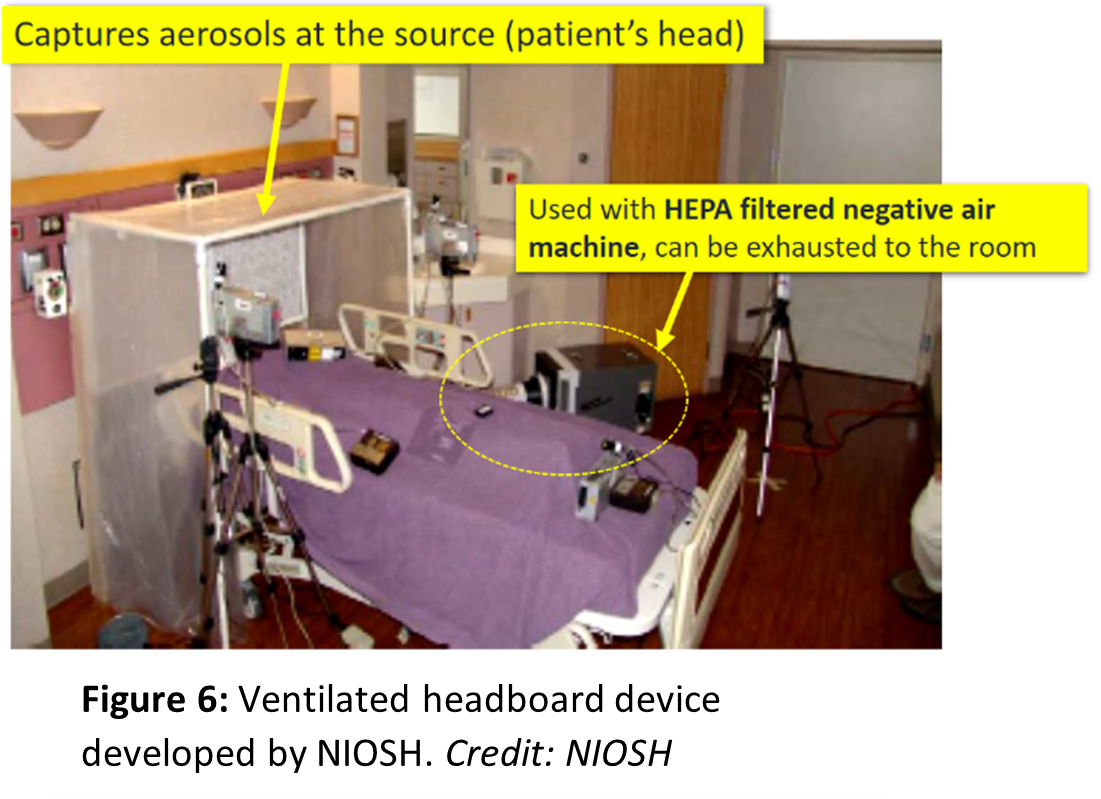

Ventilated headboards provide an additional strategy to improve the effectiveness of isolation. Ventilated headboards provide an enclosure that captures virus particles directly from the breathing zone of an infected resident before they are released into the general room air. The headboard is connected to a HEPA-filtered negative air machine that filters the contaminated air and returns clean air to the room. Ventilated headboards are only effective when the resident is in bed and breathing into the enclosed area. Further information on how to build and install these devices is provided in

National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety: Ventilated Headboards.

Footnotes

ASHRAE is a professional organization dedicated to advancing the arts and sciences of heating, ventilation, air conditioning and refrigeration.

ASHE is the American Society for Health Care Engineering.

HCAI was formerly called the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD).

References and Resources

American Society for Healthcare Engineering (ASHE),

Current/Updated Health Care Facilities Ventilation Controls and Guidelines for Management of Patients with Suspected or Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), 2021.

American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) et al.,

Alternate Care Sites Task Force, Alternate Care Site HVAC Guidebook, 2020. (PDF)

American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) et al.,

Epidemic Task Force, Building Guides, Residential Healthcare, 2021.

California Department of Health Care Access and Information (HCAI) (formerly OSHPD) “HCAI Facility Development Division COVID-19 Resources". See "Negative Pressure Room", “Policy Intent Notice 4" (describes whether HCAI will review projects related to isolation of COVID-19 patients).

California Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA),

Aerosol Transmissible Diseases Regulation, Title 8, CCR Section 5199.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),

Expedient Patient Isolation Rooms, 2020.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),

Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities, 2003.

Grosskopf, Kevin.

Ventilation in Residential Care Environments. United States: N. p., 2021. Web. doi:10.2172/1778190. (PDF)

Grosskopf, K. and E. Mousavi. 2014.

Ventilation and the Transport of Bioaerosols in Healthcare Environments. ASHRAE Journal 56(8).

Minnesota Department of Health, Office of Emergency Preparedness, Healthcare Systems Preparedness Program, Airborne Infectious Disease Management,

Methods for Temporary Negative Pressure Isolation (PDF).

National Emerging Special Pathogens Training and Education (NETEC) et al.,

Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19): Strategies for Long-term Care Facilities, 2021.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) et al.,

Engineering Controls to Reduce Airborne, Droplet and Contact Exposures During Epidemic/Pandemic Response, Expedient Patient Isolation Rooms, 2020.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) et al.,

Ventilated Headboards: Engineering Controls to Reduce Airborne, Droplet and Contact Exposures During Pandemic Response, 2020.