Start by determining your school community’s risk of heat impacts. Use the

National Weather Service (NWS) HeatRisk forecast tool to find your location’s risk level. Additional information about the HeatRisk tool is available below and on the NWS website. Access the NWS HeatRisk forecast in Spanish (en español)

Once you determine HeatRisk level,

use the

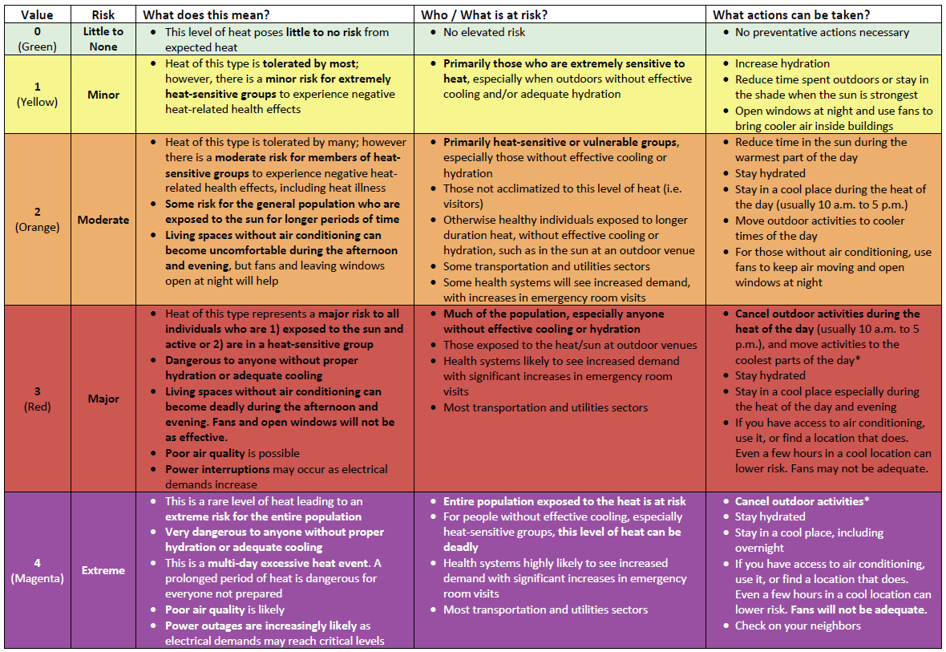

CDPH Heat Risk Grid (PDF; screenshot below -- click on) to understand what each risk level means, who is at risk and what general actions can be taken to protect those in your school community.

Access the

CDPH Heat Risk Grid in Spanish (en español ).

Click on the CDPH Heat Risk Grid (PDF) above for a high-resolution version.

The CDPH Heat Risk Grid is adapted from the NWS HeatRisk tool[10].

Spotlight: CDC HeatRisk Dashboard

In April 2024, the CDC, in partnership with the NWS, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), released the

HeatRisk Dashboard -- a user- and mobile-friendly online tool for individuals (including students, parents, guardians, and more) to look up the HeatRisk for the week by entering their zip code, along with

actions to keep themselves and their families safe . The HeatRisk Dashboard also includes information on heat and air quality (i.e., the

Air Quality Index (AQI) level for that day), as well as

heat and health guidance for healthcare professionals (which may be useful for school-based healthcare professionals).

Explore the CDC HeatRisk Dashboard >>

|

When to Cancel Sports and Other Strenuous Activities

Review the guidance below. If a circumstance is unclear or uncertain, cancel. Note, an unconditioned space is an enclosed space within a school or other building that is not cooled by a cooling system.[11]

For California Interscholastic Federation (CIF) member schools: As per California State Law Assembly Bill (AB) 1653 and CIF Bylaw 503.K. Heat Illness and 503.L. Air Quality Index Protocols, all CIF member schools must adhere to the CIF Heat Illness Prevention and Heat Acclimatization Policies as outlined in the

CIF Extreme Heat and Air Quality Policy (PDF).

|

|

Cancel all outdoor and unconditioned indoor activities

AND

(if feasible)

|

|

Reschedule all outdoor activities and unconditioned indoor activities to a different day when the HeatRisk level is no longer “Extreme” (Magenta / Level 4) or “Major” (Red / Level 3)

OR

Move to alternative activities in an air-conditioned or cooled indoor environment

|

|

Cancel all outdoor and unconditioned indoor activities

during the heat of the day

(usually 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.)

AND

(if feasible)

|

|

Reschedule all outdoor activities and unconditioned indoor activities to a cool time of the day if there is one

(for example, very early morning)

OR

Reschedule all outdoor activities and unconditioned indoor activities to a different day when the HeatRisk level is no longer “Extreme” (Magenta / Level 4) or “Major” (Red / Level 3)

OR

Move to alternative activities in an air-conditioned or cooled indoor environment

|

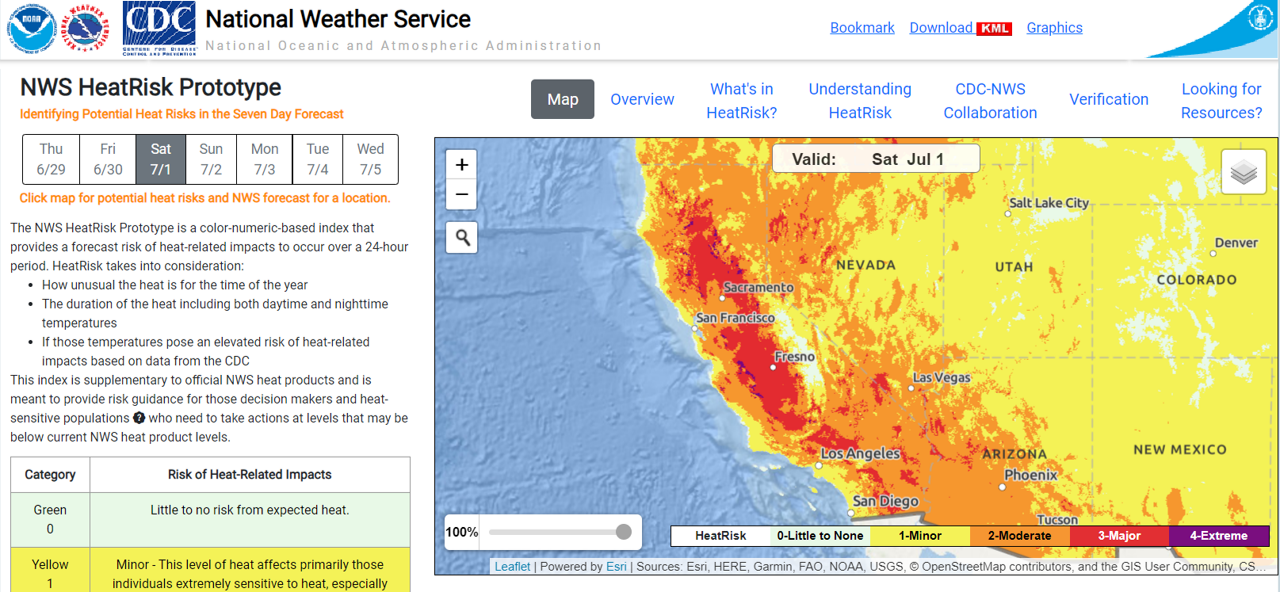

Screenshot of NWS HeatRisk forecast tool. Accessed June 29, 2023.

Identifying Potential Heat Risks in a Seven-Day Forecast

Information below adapted from the

NWS HeatRisk Overview.

Why Use HeatRisk

-

HeatRisk is a better indicator than using temperature alone

-

HeatRisk takes into consideration how unusual the heat is for your location and time of the year

-

HeatRisk accounts for how long the heat will last (including both daytime and nighttime temperatures) and for humidity

-

HeatRisk incorporates data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to determine if temperatures pose an elevated risk of heat-related health impacts

Understanding the HeatRisk Forecast:

The National Weather Service (NWS) HeatRisk tool is a color-numeric-based index that provides a forecast of the potential level of risk for heat-related impacts to occur over each day (24-hour period). The HeatRisk tool incorporates heat-health data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to influence the local thresholds and inform the approach. That level of risk is illustrated by a color/number along with identifying the groups potentially most at risk at that level. Each HeatRisk level is also accompanied by recommendations for heat protection and can serve as a useful tool for planning for upcoming heat and its associated potential risk. Based on the NWS high resolution national gridded forecast database, a daily HeatRisk value is calculated for each location from the current date through seven days in the future. HeatRisk uses the NWS’ official temperature forecast, which includes model data that takes into account urban heat islands. The National Weather Service uses this tool plus their expert judgement to declare heat advisories, watches, and warnings.

This HeatRisk tool can be used to protect lives and property from the potential risks of excessive heat and may be especially useful for those who are more easily affected by heat or those who provide support to those communities of heat-vulnerable individuals. Weather extremes generally affect historically underserved and marginalized communities the most and the HeatRisk forecast service ensures that communities have the right information at the right time to be better prepared for upcoming extreme heat.

How to Access the HeatRisk Tool:

-

Go to the NWS HeatRisk tool webpage

-

Click the magnifier icon and type in your address or location

-

Once address / location entered, the tool will display a seven-day forecast starting with the current day, including high and low temperatures and potential heat risk (with HeatRisk levels indicated by the colors green / yellow / orange / red / magenta). Additionally, information about hazardous weather conditions will be provided (for example, excessive heat warnings). See example screenshot for Sacramento, California below during the September 2022 heat wave:

NWS HeatRisk forecast, Sacramento, California. Accessed September 4, 2022.

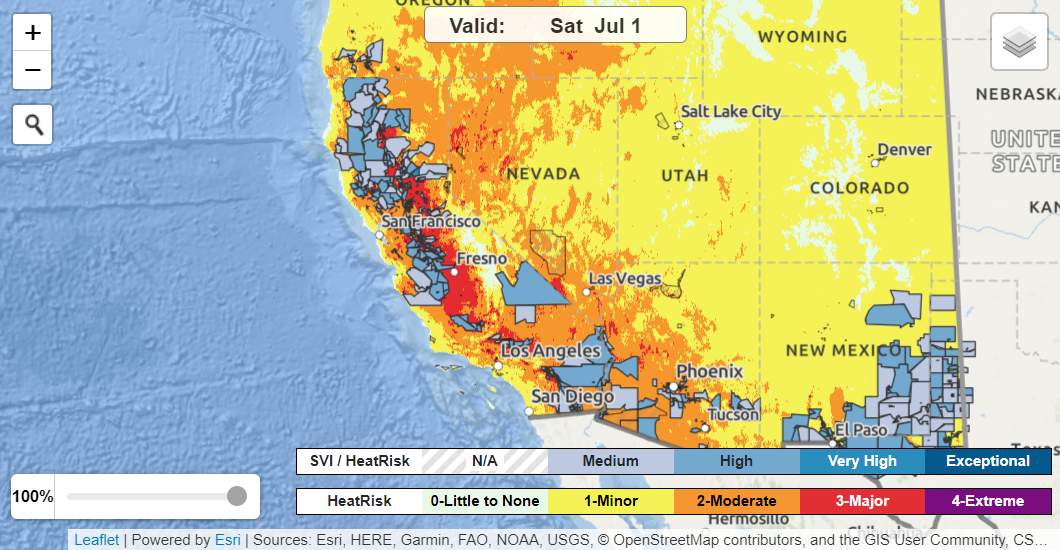

The HeatRisk tool also provides additional decision-support layers (see the “layers” icon at the upper right of the map) that allow users to view geographic boundaries (including US Counties and Tribal Lands), other NWS heat information (i.e., Heat Advisory, Excessive Heat Watch or Warning) and social vulnerability (based on the

CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index) as an overlay layer.

HeatRisk map showing US County boundaries and Social Vulnerability Index overlay. Accessed June 26, 2023.

Signs and Symptoms of Exertional Heat-Related Illness

-

Muscle cramping

-

Dizziness

-

Headache

-

Weakness

-

Hot and wet or dry skin

-

Flushed face

-

Rapid heartbeat, low blood pressure

-

Breathing very fast (hyperventilation)

-

Vomiting, diarrhea

-

Behavioral / cognitive changes* (confusion, irritability, aggressiveness, hysteria, emotional instability, impaired judgement, inappropriate behavior)

-

Drowsiness, loss of consciousness*

-

Staggering, disorientation*

-

Difficult speaking, slurred speech*

-

Seizures*

*These are signs of the most severe form of exertional heat-related illness, heat stroke, which is life threatening and requires

immediate, aggressive body cooling and medical attention (see next section for more information).

For general information on signs, symptoms and treatment of heat-related illness, visit the CDC website.

Treatment Of Exertional Heat Stroke

When exertional heat stroke (EHS) is

suspected for an athlete,

cool first and transport second. Cooling treatment must be provided immediately, before being transported by emergency medical services (EMS).[12,13]

-

Remove all equipment and extra layers of clothing

-

Cool the athlete as quickly as possible within 30 minutes via whole body cold or ice water immersion (place the athlete in a tub with ice and water approximately 35-58 degrees F).*

-

Stir water and add ice throughout cooling process.

-

If cold-water immersion is not possible (no tub), aggressively douse the athlete’s whole body with cold water. Or if that’s not possible, take the athlete to a shaded, cool area and use rotating cold, wet towels to cover as much of the body surface as possible.

-

After cooling has been initiated, activate emergency medical system by calling 9-1-1.

Exertional heat stroke has a high survival rate when immediate cooling via cold water immersion or aggressive whole-body dousing in cold water is initiated. Immediate means within 10 minutes of collapse.[12,14]

|

*The Inter-Association Task Force for Preventing Sudden Death in Secondary School Athletics Programs recommends schools having a cold-water immersion tub if a risk of EHS exists.[12]

Learn more about preventing, recognizing and treating EHS at

UConn Korey Stringer Institute – Heat Stroke

-

Personal factors. Age, obesity, dehydration, heart disease[15], mental illness, poor circulation, sunburn, pregnancy and prescription drug and alcohol use all can play a role in whether a person can cool off enough in very hot weather.

-

Exertion level. Even young and healthy people can get sick from the heat if they participate in strenuous[16] physical activities such as Physical Education during hot weather without gradually acclimatizing to hot conditions over a period of 1–2 weeks.

-

High humidity. When the humidity is high, sweat won’t evaporate as quickly. Evaporation of sweat is the main way the body can cool itself.

Who is most vulnerable to heat?

Extreme heat can affect anyone, but there are a number of factors that increase a person’s risk from extreme heat. People with greater heat sensitivity or heat vulnerability are at an increased risk of heat illness and death and include (but are not limited to) youth populations who:

-

Are exercising or doing strenuous activities outdoors (or indoors in spaces without adequate cooling) during the heat of the day – especially those not used to the level of heat expected, those who are not drinking enough fluids or those new to that type of activity

-

Attend schools or engage in school-based activities in urban areas (due to urban heat island effect), particularly at schools with more asphalt and dark surfaces and less shade, tree canopy or green spaces

-

Attend schools without air conditioning, including in under-resourced communities or geographic areas where buildings historically have not needed air conditioning (for example, coastal communities)

-

Are very young (infants and children up to four years of age are at greatest risk)

-

Are living with disabilities and/or have access and functional needs

-

Are affected by certain chronic health conditions or other illnesses

-

Are affected by certain mental health conditions

-

Are taking

certain medications (like antidepressants) or substances (like alcohol)

-

Are limited English proficient (LEP)

-

Otherwise do not have access to a reliable source of cooling and/or hydration

-

Otherwise already experience social and health inequities

Administrators, coaches or other organizers should take measures to make sure participants stay cool, stay hydrated, stay connected and stay informed. Make sure water is available during outdoor activities, including water activities. Encourage regular breaks and hydration. Evaluate conditions regularly and make appropriate adjustments – for example, postpone or reschedule practices whenever possible to be held early in the morning or late in the evening to avoid times when heat is more severe.

Closely monitor participants and ask yourself these questions:

-

Are they drinking enough water?*

-

Do they have access to air conditioning?

-

Do they need help keeping cool?

-

Are they exhibiting signs and symptoms of heat-related illness (see information above)?

Remind participants:

-

Getting too hot can make them sick.

-

Limit their outdoor activity, especially midday when the sun is hottest.

-

Pace their activity. Start activities slowly and pick up the pace gradually.

-

Drink more water than usual and don’t wait until they’re thirsty to drink more.*

-

Muscle cramping may be an early sign of heat-related illness.

-

Wear loose, lightweight, light-colored clothing.

-

Use sunscreen and reapply as needed (follow package directions).

[For Everyone] Take these steps to prevent heat-related illnesses, injuries and death during hot weather:

-

Stay in an air-conditioned indoor location as much as you can.

-

Assess your hydration and be aware of your individual hydration needs (urine color, body mass changes, thirst).*

-

Schedule outdoor activities carefully.

-

Wear loose, lightweight, light-colored clothing and sunscreen.

-

Pace yourself.

-

Take cool showers or baths to cool down.

-

Check on other participants or teammates and have someone do the same for you.

-

Monitor the environmental conditions on site using a Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) device**

-

Check the local news for health and safety updates.

-

Check the National Weather Service

HeatRisk forecast.

*Learn more about maintaining an appropriate level of hydration before, during and after exercise by visiting the

University of Connecticut (UConn) Korey Stringer Institute’ s “Hydration” webpage.

**Learn more at

UConn Korey Stringer Institute – Wet Bulb Globe Temperature Monitoring

The California Interscholastic Federation provides a free “Heat Illness Prevention” training as well as web pages outlining the identification and treatment of heat exhaustion, heat stroke, heat syncope, exertional hyponatremia and heat cramps. See: Heat Illness - California Interscholastic Federation

Protect students through heat acclimatization:

Adapted from the Korey Stringer Institute (KSI), University of Connecticut (UConn)

Acclimatization or acclimation to heat is an important factor in how a person’s body responds to and is able to cope with heat exposure. Acclimatization can be broadly defined as “a complex series of changes or adaptations that occur in response to heat stress in a controlled environment over the course of 7 to 14 days.” These changes can improve a student athlete’s ability to handle heat stress during practice or exercise.[17]

For additional information on heat acclimatization for athletes, visit the

UConn KSI “Heat Acclimatization” webpage.

Plan and prepare for heat and other emergencies:

Schools and organizations that sponsor athletics can develop an Emergency Action Plan (EAP) for managing heat and other emergencies before they occur. Having an EAP in place prepares your school community to respond immediately when an emergency happens.

For more information, explore the resources here:

Address heat in schools through built environment and nature-based solutions:

School districts and schools can help reduce heat exposure in schools and schoolyards through engineered and nature-based solutions. Examples include the following (adapted from

UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation – Protecting Californians with Heat-Resilient Schools [PDF]):

-

Improve school building envelopes (for example, insulation, double-paned windows, window shading and air sealing). From a broader climate resiliency perspective, these improvements would ideally be completed in combination with other health and safety upgrades to ensure healthy air and indoor environmental quality (for example, lead, mold and asbestos remediation).

-

Install cool roofs on schools.

-

Plant trees to provide shade outdoors, both for the buildings and play areas.

-

Install other outdoor shade structures, such as shade sails over playground equipment, outdoor dining and other outdoor common areas.

-

Decrease asphalt cover and increase cool pavements, permeable surfaces, and natural ground cover, like gardens.

-

Transition toward schoolyards with more trees and other greenery to reduce heat burden.

-

Install or improve cooling equipment (like air conditioners or heat pumps), prioritizing energy-efficient equipment whenever possible.

Consider air quality impacts during extreme heat:

Higher temperatures can lead to an increase in ozone, a harmful air pollutant.[18] Check the Air Quality Index (AQI) in your area to determine if air quality is healthy or unhealthy and what steps to take to protect health. Learn more by visiting the

AirNow website.

Additionally, hotter temperatures and drought conditions can increase the risk of wildfires. Wildfire smoke can severely impact air quality locally and downwind. Heath effects from exposure to particulate matter in wildfire smoke can include eye and lung irritation, exacerbation of asthma and other impacts.[19]

For additional guidance, please see the

California Department of Education’s School Air Quality Activity Recommendations. (PDF)

Additional Resources:

Heat Illness Prevention for School (and Other) Workers:

From Cal/OHSA / California Department of Industrial Relations (DIR)

Further Reading

References

[1]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Extreme Heat and Your Health.

[2]

Tracking California. Heat Related Deaths Summary Tables.

[3] Heat Illness Among High School Athletes --- United States, 2005--2009. MMWR. 2010.

[4]

HeatRisk Overview.

[5] Epstein Y & Yanovich R. 2019. Heatstroke. New England Journal of Medicine, 380(25), 2449-2459.

[6]

CDC. Symptoms of Heat-Related Illness.

[7]

Kerr Z, Casa D, Marshall S and Dawn Comstock, R. 2013. Epidemiology of Exertional Heat Illness Among U.S. High School Athletes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. Vol. 44; Issue 1; P8-14.

[8]

Bergeron M, McKeag D, Casa D, et al. 2005. Youth Football: Heat Stress and Injury Risk. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise . 37(8):p 1421-1430.

[9]

USA Football - Heat Preparedness and Hydration.

[10] National Weather Service (NWS).

HeatRisk - Understanding HeatRisk.

[11]

U.S. Department of Energy - Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. What Are Space Conditioning Types?

[12] The Inter-Association Task Force for Preventing Sudden Death in Secondary School Athletics Programs: Best-Practices Recommendations.

[13]

UConn KSI - Exertional Heat Stroke Treatment.

[14] McDermott B, Casa D, Ganio M, et al. 2009. Acute Whole-Body Cooling for Exercise-Induced Hyperthermia: A Systematic Review. Journal of Athletic Training. Jan-Feb; 44(1): 84–93.

[15] Note that common illnesses can also be exacerbated by extreme heat including autoimmune conditions; asthma, COPD and allergies; migraines; heart disease; and autoimmune diseases including multiple sclerosis (MS), lupus and rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

[16] Vigorous activity is defined by the Centers for Disease Control as activities greater than 6.0 METs.

Specific examples can be found here.

[17]

UConns KSI - Heat Acclimatization.

[18]

CDC. Protect Yourself From the Dangers of Extreme Heat.

[19]

California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA). Wildfires.